Baltimore IMC : http://www.baltimoreimc.org

News :: [none]

People's Sovereignty Movement Gathers to Challenge Corporate Rule

This is an account of a July 5, 2004 workshop in Santa Rosa, CA on the topic of challenging the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights. The gathering featured Richard Grossman, who has researched and written extensively on challenging corporate constitutional rights, and Thomas Linzey, an attorney from Pennsylvania who has helped several townships enact ordinances that reassert the people's sovereignty over corporations. About fifty people attended the workshop.

.

CLICK to SEE: 10-Session Baltimore Corporate Study Group Forming

.

CLICK to SEE: 10-Session Baltimore Corporate Study Group Forming

.

Introduction: On July 5, 2004 about fifty people gathered for a day-long workshop at the New College of California, in Santa Rosa, CA. The workshop focused on ways to challenge the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights. Most participants were from Northern California; however, a couple of people attended from Washington, and Arizona. The featured participants, Thomas Linzey and Richard Grossman, came from Pennsylvania and New Jersey respectively. Grossman, co-founder of the Program on Corporations Law and Democracy (POCLAD), has researched and written extensively on challenging corporate constitutional rights. Linzey, an attorney and co-founder of the Pennsylvania-based Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), has made his mark by drafting ordinances for local governments that reassert direct, democratic control over corporations. During the workshop, Grossman and Linzey led discussions on ways to reassert the people's sovereignty over our governing institutions and corporations.

Reflecting on Sovereignty

The American Revolution was founded on the principle that the people have a natural, inalienable right to self-determination. We are free, and thus free to self-govern*. All power is derived from the people and vested in the people. That is, the people are sovereign. However, it seems that contemporary people have forgotten what it means to be sovereign. Reflecting on a brief historical story will serve as a refresher.

Once upon a time kings were the sovereigns; they were all-powerful. They had the power to charter corporations whereby capital could be consolidated and directed to benefit both the King and those who were granted corporate privileges. In 1628 King Charles I chartered the Massachusetts Bay Company to exploit the resources of the New World. At one point, the King sent representatives to assess whether the Company was abiding by the terms of its charter, and asked to review the Company's books. When the company resisted, the Crown responded, "The King did not grant away his sovereignty over you when he made you a corporation."

This story is not only a refresher on the meaning of "sovereignty," it also suggests that the people have the legitimacy to reassert their control over corporations. Workshop participants in Santa Rosa, CA discussed ways people are currently doing this at the local government level.

Challenging Corporate Constitutional Rights at the Local Government Level

Corporations are not mentioned in the US Constitution. The founders of our nation recognized the risks associated with the potential accumulation of power by corporations. In an effort to contain this power, only states were allowed to charter corporations, the rationale being that states are closer to the people than the federal government.

Before the Civil War, obtaining a corporate charter was considered a privilege. However, over time, state-created corporations gradually amassed “rights” under the US Constitution, protected by the federal government. These rights do not appear in the US Constitution, but instead were granted to corporations by the US Supreme Court.

These "rights" include recognition of corporations as a person with access to due process and equal protection under the 14th Amendment, originally adopted to recognize African Americans as “persons.” As "persons," telecommunications corporations, seeking to locate transmission towers, have used the 1964 Civil Rights Act's protections from discrimination to force their way into communities. Corporations have also used protection from discrimination to force communities to accept big box retail stores that undermine their local economy. Corporations have gained 4th Amendment protection from searches thereby enabling them to hide records and evade meaningful environmental and worker safety inspections. Corporations have gained various "free speech" rights under the 1st Amendment including the recognition of corporate money, used in election and ballot initiative campaigns, as a form of protected political speech. The right "not to speak" was expanded for corporations by the Supreme Court in 1996 when it overturned a Vermont law requiring the labeling of all products containing bovine growth hormone (International Dairy Foods Association vs Amestoy). (Mayer, 1990) ( WILPF Timeline) (Grossman, et, al. 2003).

The people who met on July 5 in Santa Rosa don't classify themselves with a label, but are engaged in what could be called “the people's sovereignty movement.” They challenge the legitimacy of the US Supreme Court, or any other arm of government, “to bestow upon corporations the immense governing authority” implicit in the conferral of constitutional rights. They base this challenge on a solid founding principle; no governing entity may grant away the people's right to a functional republican form of government. They contend that excessive corporate power has undermined this basic right of the people. (POCLAD, 2003) (See Also, Grossman, et, al, 2003).

Rather than try to change Supreme Court decisions, the people's sovereignty movement is building popular support for eliminating corporate constitutional rights; they are urging their fellow citizens to effectively say, "We hold ultimate authority, and despite what the Supreme Court says, we did not grant away our sovereignty over you when we made you a corporation." So, what concrete steps does one take to make this tangible?

Some examples from other venues provide guidance. Perhaps you have heard about cities, and even the State of Hawaii, passing resolutions that reject the legitimacy of the USA PATRIOT Act. At least one city, Arcata, CA, passed a binding ordinance refusing compliance with elements of the Act. Local jurisdictions across the country also rejected the legitimacy of the Iraq war by passing resolutions expressing their opposition.

This general strategy of harnessing local governing institutions to assert a direct popular challenge of federal power creates a "crisis of jurisdiction." By doing this, they pose the following question, "Who's position is more legitimate, the local government, which is closer to the people, or the federal government?" If these local challenges gain a majority of the people's support, then the principle of "sovereignty" kicks in; the legitimacy of the local perspective sits on the bedrock foundation of democracy, thereby undermining the legitimacy of the federal perspective. Social change derived from this root-level rationale is also the basis of the growing movement to challenge corporate power.

There are many ways of mounting local challenges. Attorney Thomas Linzey is applying innovative tactics for challenging corporate constitutional rights in Pennsylvania. Linzey described how he has worked with townships in Pennsylvania to draft non-binding resolutions that reject the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights. The townships are motivated by their shared experience of failing to be able stop corporate factory farms and similar infringements. A number of other townships in Pennsylvania are going beyond non-binding resolutions to enact binding ordinances (laws).

The morning session of the workshop focused on a specific case study about the township of St. Thomas, PA, which is being threatened by a quarry-asphalt-cement corporation. They are confronting the St. Thomas Development Corporation (STD Corp.), which was created by its parent corporation to undertake the quarry project. By giving birth to the STD Corp. as a separate entity, the parent corporation hides its own identity and shields itself from liability for the actions of its offspring.

Richard Grossman explained that the town could confront STD Corp's actions at the regulatory level, focusing on "proper quarry configurations, or on the factory's potential for ravaging public health." Members of Friends and Residents of St. Thomas Township (FROST) have chosen "not [to] debate state officials over how many feet this corporate project should be from the elementary school." Instead, FROST, with assistance from Linzey, has turned to a more principled defense. They are challenging STD Corp's claims to constitutional rights, which allow it to do harm to the community without recourse to remedy. (Grossman, 2004)

"Having analyzed this corporation's invasion of their community in historical and constitutional contexts," Grossman says that the community "...concluded that the Pennsylvania legislature enabled corporate directors to violate their privileges and immunities in the US Constitution. Learning from the Abolition and Anti-Segregation struggles..." the community is taking actions "...to dramatize government complicity in the corporation's "legal" violation of citizen's rights." (Grossman, 2004)

Linzey described a labor-intensive process that he has repeated in several Pennsylvania townships. The broad strategy is to assert the people's sovereign rights at a local government level through what he calls a “protective ordinance.” This is a law that is idle until a corporation infringes on the town. If a corporation inflicts harm on the town, and asserts its constitutional right to do so, then the local attorneys can invoke the protective law in their defense. This sets up the crisis of jurisdiction. By adopting this strategy, the town sets the agenda for challenging the conventional rules on both legal and political levels.

Linzey's strategy in St. Thomas Township makes use of a compelling legal perspective that appeals to common sense. It begins by recognizing our inalienable right to self-govern. Based on this, we established a republican form of government to secure those rights. Within this framework, the majority of the sovereign people make decisions regarding those rights and other matters, with protections for the minority. State governments give “privileges” to corporations, including the privilege to exist. However, corporations, run by a minority, often deny rights of people, which cause harms. Grossman notes, "Invoking the people's constitutional maxim 'where there is harm, there must be remedy,'" the sovereign people petition the government for a remedy. By this strategy, our governmental institutions are forced to confront whether the rights of self-governing people have primacy over those of the corporation. When a local government, like St. Thomas Township, PA, sides with the people, the state and federal government are revealed to be siding with the corporation. This is the crisis of jurisdiction.

Richard Grossman notes that this crisis is, "not about the corporation. It's about the state enabling the corporation." Once the state and federal governments are revealed to be siding with the corporation, and against the popular will of the people, they are isolated. It becomes easier to expose contradictions that are otherwise lost in complexity. For example, a corporation must either be a public or private entity. If it is a public entity, then the state is compelled to enforce remedies that protect the majority from corporate infringements. Alternatively, if a corporation is a private entity, and controlling their harms is beyond the control of the state, a logical flaw is exposed, because the State chartered the corporation. This contradiction in logic was expressed in a dissenting opinion by Justice Byron White, after the US Supreme Court, in Bellotti (1978), granted corporations the right to equate money with political free speech:

“It has long been recognized, however, that the special status of corporations has placed them in a position to control vast amounts of economic power which, if not regulated, dominate not only the economy but also the very heart of our democracy, the electoral process... The State need not permit its own creation to consume it.”

Supreme Court Justice Byron White

As noted by Justice White, it is well established that corporations have amassed so much wealth that they assert a dominant influence over the institutions of the electoral process, law-making and the creation of regulations that specify how laws will be implemented. Corporations have also asserted influence over judicial theory, the make-up of courts, and court proceedings, thus biasing judicial precedents (court-made law). It is noteworthy that these are the institutions by which we exercise our democracy. Many sophisticated issue advocacy groups have learned how to fight corporate harms within the regulatory and judicial system, even winning on occasion; however, despite these short-term "wins," the corporations typically prevail in the long-term by out spending and out waiting its challengers.

Recognizing that corporate lobbyists often write the state corporate code and other laws, Linzey commented, "Courts interpret laws, which we didn't write. Then we expect the court to decide in our favor? How crazy is that?" Rather than struggle within the convoluted regulatory scheme, a growing number of people, like Linzey, are heeding the words of Henry David Thoreau, who said, "There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil for one who is striking at the root."

It is important to remember that the corporate form of a business enterprise is not the only form. One can conduct business without being a corporation. The corporate form was originally intended to be a privileged form of business conferred by the people through their state government with the expectation that the corporate entity was responsible for creating a greater social good. If it did not, the people could withdraw this privilege, effectively saying, "Do business without the privileges of a corporate form."

As you might expect, Linzey is attracting the wrath of the St. Thomas Development Corporation. The corporation is not only pressing US District Court Judge Yvette Kane to throw out FROST's legal challenge, but is asking the Court to punish Linzey.

Linzey and Grossman were clear that resolutions and ordinances are not in themselves the goal. Linzey noted, "A resolution is OK as long as it is part of a larger plan." The process is the goal, and the confrontational response from powerful corporate interests is an intended part of that process.

Grossman, who has been engaged in this line of thinking for over a decade, noted that this movement necessitates a long view. He also gave a sobering comparison with past movements. During the American Revolution, the British eventually said, "no more negotiating," and the impasse led to a violent war. During the challenge of the economic system built upon slavery, the slave owners eventually said, "no more negotiating," and the impasse led to a violent war. During the challenge of South African Apartheid, after years of violence, the South African power elite came to the brink, and decided to negotiate rather than risk further violence. Grossman suggested that a similar analogy applies to the struggle to reassert the people's sovereignty over corporate power, implying the likelihood of a future day of reckoning. With this in mind, and the pending effort to silence Thomas Linzey, Grossman noted the importance of rapidly growing this movement before it can be crushed.

The afternoon workshop session agenda had originally included Green Party presidential candidate David Cobb. Cobb was unable to attend the workshop due to obligations associated with his nomination the week preceding the workshop. CLICK for Related Article Kirsten Lambertsen and Bill Meyers spoke on behalf of Cobb who is himself very well versed in the language of challenging corporate rule.

Lambertsen spoke briefly about her efforts to enact a San Fransisco City Council resolution that rejects corporate claims to constitutional rights. Lambertsen also informed the group that she is coordinating a national initiative to set up information tables at showings of the new documentary "The Corporation." The City Council of Berkeley, CA unanimously enacted a similar resolution on June 15, 2004. According to one of the leading organizers in the Berkeley effort, the most conservative City Council member said, "it is common sense." SEE Berkeley Resolution Similar resolutions have been passed in the towns of Point Arena, CA, and Arcata, CA. SEE Point Arena and Arcata Resolutions

Another workshop participant, Paul Cienfuego, briefly described a unique strategy that he helped pioneer in Arcata, CA. In 1998, Arcata voters passed a ballot referendum (citizen-written law) requesting that their City Council hold two town hall meetings on the topic: "Can we have democracy when large corporations wield so much power and wealth under law?" The referendum also required their City government to "establish, through the creation of an official committee, policies and programs which ensure democratic control over corporations conducting business within the City." Taking no shortcuts, interested citizens and small business owners participated in a dialogue, which laid a foundation for making informed policies about limiting corporate powers. One tangible result has been the adoption of a carefully crafted ordinance that limits the number of chain restaurants in Arcata’s Historic District.

Later in the afternoon Grossman and Linzey addressed questions. Topics included how this new paradigm might be applied to WalMart, how to address property rights, whether or not it is more effective to start with a specific local issue or whether a campaign to challenge corporate constitutional rights can be waged more broadly, what would the future look like if corporate constitutional rights were removed, ideas for waging a state-wide effort tied to the protection of public drinking water supplies, additional detailed discussion of the mechanics of Linzey's work, the use of local referenda to ban the growth and distribution of genetically engineered agricultural products, and the potential of creating a collective of attorneys to assist local efforts.

Parting Thoughts

After the workshop, several participants shared personal thoughts regarding their involvement. Jacqui Brown-Miller, of Olympia, WA, said she came because she "wanted to discuss strategy with other natural persons on how to restore democracy in America."

Deb Lagutaris said that she "decided one of the most effective ways to shift the paradigm was to go to law school to find out how corporations work." "I have three grand children and don't want their only option in life to be working for a sweat shop." "I learned about the Program on Corporations Law and Democracy www.POCLAD.org when doing research for my senior thesis on limiting the power of corporations."

Like Brown-Miller and others at the workshop, Lagutaris has also been involved with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Every three years, WILPF members go through a very deliberative process to select the campaigns on which they will dedicate their resources. One of the few campaigns they launched several years ago is called “Challenging Corporate Power; Asserting the People's Rights.” For those people who are inspired to be a part of this multi-generational struggle, WILPF, in concert with POCLAD, has developed a 10-part self-study packet. It serves as a good starting point to consider.

SEE WILPF 10-Part Study Packet

Notes:

* We are also free to agree to having no government (anarchism), but that would take a few constitutional amendments ;-)

REFERENCES:

Grossman, Richard, “Confronting the Corporate Constitution in Pennsylvania,” June 9, 2004. This article, was circulated to workshop participants as background prior to the workshop. (See May 21 “First Stone” entry, by Joel Bleifuss at In These Times web site: www.inthesetimes.com/site/main/firststone )

Grossman, R., Linzey, T., and Brennen, D., “Model Legal Brief to Eliminate Corporate Rights,” original draft, Fall, 2003.

Find it at www.poclad.org or www.celdf.org

Mayer, Carl, "Personalizing the Impersonal: Corporations and the Bill of Rights," Hastings Law Journal, V 41, No 3, March 1990. Available at http://reclaimdemocracy.org/personhood/mayer_personalizing.html

POCLAD (Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy), Correspondence to POCLAD Supporters, including a summary of the 'Model Legal Brief to Eliminate Corporate Rights', December, 2003.

WILPF Timeline of US Supreme Court decisions affecting corporate rights.

http://www.wilpf.org/corp/ACP/CP_article+timeline.pdf

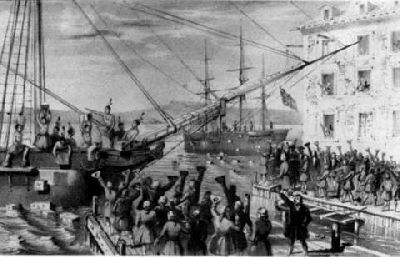

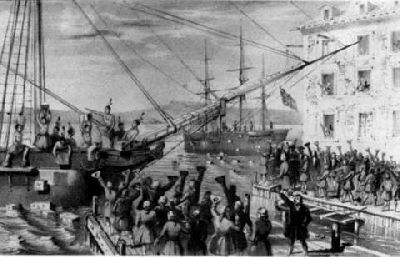

Gathering of people in Santa Rosa, CA to discuss ways of challenging corporate constitutional rights. July 5, 2004

Introduction: On July 5, 2004 about fifty people gathered for a day-long workshop at the New College of California, in Santa Rosa, CA. The workshop focused on ways to challenge the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights. Most participants were from Northern California; however, a couple of people attended from Washington, and Arizona. The featured participants, Thomas Linzey and Richard Grossman, came from Pennsylvania and New Jersey respectively. Grossman, co-founder of the Program on Corporations Law and Democracy (POCLAD), has researched and written extensively on challenging corporate constitutional rights. Linzey, an attorney and co-founder of the Pennsylvania-based Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), has made his mark by drafting ordinances for local governments that reassert direct, democratic control over corporations. During the workshop, Grossman and Linzey led discussions on ways to reassert the people's sovereignty over our governing institutions and corporations.

Reflecting on Sovereignty

The American Revolution was founded on the principle that the people have a natural, inalienable right to self-determination. We are free, and thus free to self-govern*. All power is derived from the people and vested in the people. That is, the people are sovereign. However, it seems that contemporary people have forgotten what it means to be sovereign. Reflecting on a brief historical story will serve as a refresher.

The Boston Tea Party was triggered by excesses of corporations chartered by England to exploit the colonies.

Once upon a time kings were the sovereigns; they were all-powerful. They had the power to charter corporations whereby capital could be consolidated and directed to benefit both the King and those who were granted corporate privileges. In 1628 King Charles I chartered the Massachusetts Bay Company to exploit the resources of the New World. At one point, the King sent representatives to assess whether the Company was abiding by the terms of its charter, and asked to review the Company's books. When the company resisted, the Crown responded, "The King did not grant away his sovereignty over you when he made you a corporation."

This story is not only a refresher on the meaning of "sovereignty," it also suggests that the people have the legitimacy to reassert their control over corporations. Workshop participants in Santa Rosa, CA discussed ways people are currently doing this at the local government level.

Challenging Corporate Constitutional Rights at the Local Government Level

Corporations are not mentioned in the US Constitution. The founders of our nation recognized the risks associated with the potential accumulation of power by corporations. In an effort to contain this power, only states were allowed to charter corporations, the rationale being that states are closer to the people than the federal government.

Before the Civil War, obtaining a corporate charter was considered a privilege. However, over time, state-created corporations gradually amassed “rights” under the US Constitution, protected by the federal government. These rights do not appear in the US Constitution, but instead were granted to corporations by the US Supreme Court.

These "rights" include recognition of corporations as a person with access to due process and equal protection under the 14th Amendment, originally adopted to recognize African Americans as “persons.” As "persons," telecommunications corporations, seeking to locate transmission towers, have used the 1964 Civil Rights Act's protections from discrimination to force their way into communities. Corporations have also used protection from discrimination to force communities to accept big box retail stores that undermine their local economy. Corporations have gained 4th Amendment protection from searches thereby enabling them to hide records and evade meaningful environmental and worker safety inspections. Corporations have gained various "free speech" rights under the 1st Amendment including the recognition of corporate money, used in election and ballot initiative campaigns, as a form of protected political speech. The right "not to speak" was expanded for corporations by the Supreme Court in 1996 when it overturned a Vermont law requiring the labeling of all products containing bovine growth hormone (International Dairy Foods Association vs Amestoy). (Mayer, 1990) ( WILPF Timeline) (Grossman, et, al. 2003).

The people who met on July 5 in Santa Rosa don't classify themselves with a label, but are engaged in what could be called “the people's sovereignty movement.” They challenge the legitimacy of the US Supreme Court, or any other arm of government, “to bestow upon corporations the immense governing authority” implicit in the conferral of constitutional rights. They base this challenge on a solid founding principle; no governing entity may grant away the people's right to a functional republican form of government. They contend that excessive corporate power has undermined this basic right of the people. (POCLAD, 2003) (See Also, Grossman, et, al, 2003).

Rather than try to change Supreme Court decisions, the people's sovereignty movement is building popular support for eliminating corporate constitutional rights; they are urging their fellow citizens to effectively say, "We hold ultimate authority, and despite what the Supreme Court says, we did not grant away our sovereignty over you when we made you a corporation." So, what concrete steps does one take to make this tangible?

Some examples from other venues provide guidance. Perhaps you have heard about cities, and even the State of Hawaii, passing resolutions that reject the legitimacy of the USA PATRIOT Act. At least one city, Arcata, CA, passed a binding ordinance refusing compliance with elements of the Act. Local jurisdictions across the country also rejected the legitimacy of the Iraq war by passing resolutions expressing their opposition.

People are challenging the legitimacy of federal policy by passing resolutions and ordinances at the local government level. This scene depicts people protesting the USA PATRIOT Act in a 4th of July parade, in Mt. Shasta, CA.

This general strategy of harnessing local governing institutions to assert a direct popular challenge of federal power creates a "crisis of jurisdiction." By doing this, they pose the following question, "Who's position is more legitimate, the local government, which is closer to the people, or the federal government?" If these local challenges gain a majority of the people's support, then the principle of "sovereignty" kicks in; the legitimacy of the local perspective sits on the bedrock foundation of democracy, thereby undermining the legitimacy of the federal perspective. Social change derived from this root-level rationale is also the basis of the growing movement to challenge corporate power.

There are many ways of mounting local challenges. Attorney Thomas Linzey is applying innovative tactics for challenging corporate constitutional rights in Pennsylvania. Linzey described how he has worked with townships in Pennsylvania to draft non-binding resolutions that reject the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights. The townships are motivated by their shared experience of failing to be able stop corporate factory farms and similar infringements. A number of other townships in Pennsylvania are going beyond non-binding resolutions to enact binding ordinances (laws).

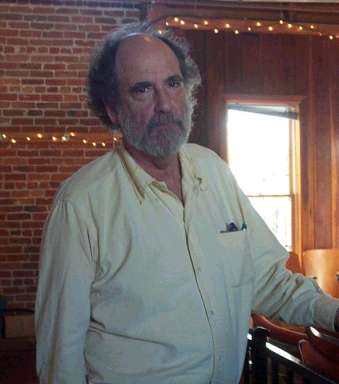

Attorney Thomas Linzey is helping Pennsylvania townships write protective ordinances that challenge the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights.

The morning session of the workshop focused on a specific case study about the township of St. Thomas, PA, which is being threatened by a quarry-asphalt-cement corporation. They are confronting the St. Thomas Development Corporation (STD Corp.), which was created by its parent corporation to undertake the quarry project. By giving birth to the STD Corp. as a separate entity, the parent corporation hides its own identity and shields itself from liability for the actions of its offspring.

Richard Grossman explained that the town could confront STD Corp's actions at the regulatory level, focusing on "proper quarry configurations, or on the factory's potential for ravaging public health." Members of Friends and Residents of St. Thomas Township (FROST) have chosen "not [to] debate state officials over how many feet this corporate project should be from the elementary school." Instead, FROST, with assistance from Linzey, has turned to a more principled defense. They are challenging STD Corp's claims to constitutional rights, which allow it to do harm to the community without recourse to remedy. (Grossman, 2004)

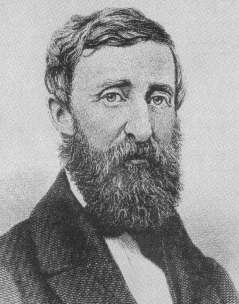

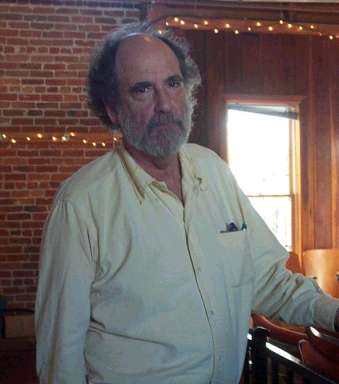

Richard Grossman, co-founder of POCLAD, has researched and written extensively on the basis of sovereign people challenging corporate power.

"Having analyzed this corporation's invasion of their community in historical and constitutional contexts," Grossman says that the community "...concluded that the Pennsylvania legislature enabled corporate directors to violate their privileges and immunities in the US Constitution. Learning from the Abolition and Anti-Segregation struggles..." the community is taking actions "...to dramatize government complicity in the corporation's "legal" violation of citizen's rights." (Grossman, 2004)

Linzey described a labor-intensive process that he has repeated in several Pennsylvania townships. The broad strategy is to assert the people's sovereign rights at a local government level through what he calls a “protective ordinance.” This is a law that is idle until a corporation infringes on the town. If a corporation inflicts harm on the town, and asserts its constitutional right to do so, then the local attorneys can invoke the protective law in their defense. This sets up the crisis of jurisdiction. By adopting this strategy, the town sets the agenda for challenging the conventional rules on both legal and political levels.

Linzey's strategy in St. Thomas Township makes use of a compelling legal perspective that appeals to common sense. It begins by recognizing our inalienable right to self-govern. Based on this, we established a republican form of government to secure those rights. Within this framework, the majority of the sovereign people make decisions regarding those rights and other matters, with protections for the minority. State governments give “privileges” to corporations, including the privilege to exist. However, corporations, run by a minority, often deny rights of people, which cause harms. Grossman notes, "Invoking the people's constitutional maxim 'where there is harm, there must be remedy,'" the sovereign people petition the government for a remedy. By this strategy, our governmental institutions are forced to confront whether the rights of self-governing people have primacy over those of the corporation. When a local government, like St. Thomas Township, PA, sides with the people, the state and federal government are revealed to be siding with the corporation. This is the crisis of jurisdiction.

Richard Grossman notes that this crisis is, "not about the corporation. It's about the state enabling the corporation." Once the state and federal governments are revealed to be siding with the corporation, and against the popular will of the people, they are isolated. It becomes easier to expose contradictions that are otherwise lost in complexity. For example, a corporation must either be a public or private entity. If it is a public entity, then the state is compelled to enforce remedies that protect the majority from corporate infringements. Alternatively, if a corporation is a private entity, and controlling their harms is beyond the control of the state, a logical flaw is exposed, because the State chartered the corporation. This contradiction in logic was expressed in a dissenting opinion by Justice Byron White, after the US Supreme Court, in Bellotti (1978), granted corporations the right to equate money with political free speech:

“It has long been recognized, however, that the special status of corporations has placed them in a position to control vast amounts of economic power which, if not regulated, dominate not only the economy but also the very heart of our democracy, the electoral process... The State need not permit its own creation to consume it.”

Supreme Court Justice Byron White

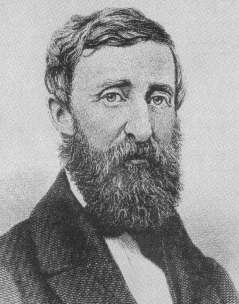

A small number of people are challenging corporate constitutional rights by heeding the words of Henry David Thoreau, who said, "There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil for one who is striking at the root."

As noted by Justice White, it is well established that corporations have amassed so much wealth that they assert a dominant influence over the institutions of the electoral process, law-making and the creation of regulations that specify how laws will be implemented. Corporations have also asserted influence over judicial theory, the make-up of courts, and court proceedings, thus biasing judicial precedents (court-made law). It is noteworthy that these are the institutions by which we exercise our democracy. Many sophisticated issue advocacy groups have learned how to fight corporate harms within the regulatory and judicial system, even winning on occasion; however, despite these short-term "wins," the corporations typically prevail in the long-term by out spending and out waiting its challengers.

Recognizing that corporate lobbyists often write the state corporate code and other laws, Linzey commented, "Courts interpret laws, which we didn't write. Then we expect the court to decide in our favor? How crazy is that?" Rather than struggle within the convoluted regulatory scheme, a growing number of people, like Linzey, are heeding the words of Henry David Thoreau, who said, "There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil for one who is striking at the root."

"There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil for one who is striking at the root."

- Henry David Thoreau

- Henry David Thoreau

It is important to remember that the corporate form of a business enterprise is not the only form. One can conduct business without being a corporation. The corporate form was originally intended to be a privileged form of business conferred by the people through their state government with the expectation that the corporate entity was responsible for creating a greater social good. If it did not, the people could withdraw this privilege, effectively saying, "Do business without the privileges of a corporate form."

As you might expect, Linzey is attracting the wrath of the St. Thomas Development Corporation. The corporation is not only pressing US District Court Judge Yvette Kane to throw out FROST's legal challenge, but is asking the Court to punish Linzey.

Linzey and Grossman were clear that resolutions and ordinances are not in themselves the goal. Linzey noted, "A resolution is OK as long as it is part of a larger plan." The process is the goal, and the confrontational response from powerful corporate interests is an intended part of that process.

Grossman, who has been engaged in this line of thinking for over a decade, noted that this movement necessitates a long view. He also gave a sobering comparison with past movements. During the American Revolution, the British eventually said, "no more negotiating," and the impasse led to a violent war. During the challenge of the economic system built upon slavery, the slave owners eventually said, "no more negotiating," and the impasse led to a violent war. During the challenge of South African Apartheid, after years of violence, the South African power elite came to the brink, and decided to negotiate rather than risk further violence. Grossman suggested that a similar analogy applies to the struggle to reassert the people's sovereignty over corporate power, implying the likelihood of a future day of reckoning. With this in mind, and the pending effort to silence Thomas Linzey, Grossman noted the importance of rapidly growing this movement before it can be crushed.

The afternoon workshop session agenda had originally included Green Party presidential candidate David Cobb. Cobb was unable to attend the workshop due to obligations associated with his nomination the week preceding the workshop. CLICK for Related Article Kirsten Lambertsen and Bill Meyers spoke on behalf of Cobb who is himself very well versed in the language of challenging corporate rule.

Lambertsen spoke briefly about her efforts to enact a San Fransisco City Council resolution that rejects corporate claims to constitutional rights. Lambertsen also informed the group that she is coordinating a national initiative to set up information tables at showings of the new documentary "The Corporation." The City Council of Berkeley, CA unanimously enacted a similar resolution on June 15, 2004. According to one of the leading organizers in the Berkeley effort, the most conservative City Council member said, "it is common sense." SEE Berkeley Resolution Similar resolutions have been passed in the towns of Point Arena, CA, and Arcata, CA. SEE Point Arena and Arcata Resolutions

Another workshop participant, Paul Cienfuego, briefly described a unique strategy that he helped pioneer in Arcata, CA. In 1998, Arcata voters passed a ballot referendum (citizen-written law) requesting that their City Council hold two town hall meetings on the topic: "Can we have democracy when large corporations wield so much power and wealth under law?" The referendum also required their City government to "establish, through the creation of an official committee, policies and programs which ensure democratic control over corporations conducting business within the City." Taking no shortcuts, interested citizens and small business owners participated in a dialogue, which laid a foundation for making informed policies about limiting corporate powers. One tangible result has been the adoption of a carefully crafted ordinance that limits the number of chain restaurants in Arcata’s Historic District.

The City of Arcata, CA is pioneering ways of asserting the people's sovereignty over corporations, thereby preserving their political freedom and democracy.

Later in the afternoon Grossman and Linzey addressed questions. Topics included how this new paradigm might be applied to WalMart, how to address property rights, whether or not it is more effective to start with a specific local issue or whether a campaign to challenge corporate constitutional rights can be waged more broadly, what would the future look like if corporate constitutional rights were removed, ideas for waging a state-wide effort tied to the protection of public drinking water supplies, additional detailed discussion of the mechanics of Linzey's work, the use of local referenda to ban the growth and distribution of genetically engineered agricultural products, and the potential of creating a collective of attorneys to assist local efforts.

Parting Thoughts

After the workshop, several participants shared personal thoughts regarding their involvement. Jacqui Brown-Miller, of Olympia, WA, said she came because she "wanted to discuss strategy with other natural persons on how to restore democracy in America."

Deb Lagutaris said that she "decided one of the most effective ways to shift the paradigm was to go to law school to find out how corporations work." "I have three grand children and don't want their only option in life to be working for a sweat shop." "I learned about the Program on Corporations Law and Democracy www.POCLAD.org when doing research for my senior thesis on limiting the power of corporations."

The Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy (POCLAD) advocates a the paradigm shift of challenging the legitimacy of corporate constitutional rights, rather than asking corporations to be nice.

Like Brown-Miller and others at the workshop, Lagutaris has also been involved with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Every three years, WILPF members go through a very deliberative process to select the campaigns on which they will dedicate their resources. One of the few campaigns they launched several years ago is called “Challenging Corporate Power; Asserting the People's Rights.” For those people who are inspired to be a part of this multi-generational struggle, WILPF, in concert with POCLAD, has developed a 10-part self-study packet. It serves as a good starting point to consider.

SEE WILPF 10-Part Study Packet

Notes:

* We are also free to agree to having no government (anarchism), but that would take a few constitutional amendments ;-)

REFERENCES:

Grossman, Richard, “Confronting the Corporate Constitution in Pennsylvania,” June 9, 2004. This article, was circulated to workshop participants as background prior to the workshop. (See May 21 “First Stone” entry, by Joel Bleifuss at In These Times web site: www.inthesetimes.com/site/main/firststone )

Grossman, R., Linzey, T., and Brennen, D., “Model Legal Brief to Eliminate Corporate Rights,” original draft, Fall, 2003.

Find it at www.poclad.org or www.celdf.org

Mayer, Carl, "Personalizing the Impersonal: Corporations and the Bill of Rights," Hastings Law Journal, V 41, No 3, March 1990. Available at http://reclaimdemocracy.org/personhood/mayer_personalizing.html

POCLAD (Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy), Correspondence to POCLAD Supporters, including a summary of the 'Model Legal Brief to Eliminate Corporate Rights', December, 2003.

WILPF Timeline of US Supreme Court decisions affecting corporate rights.

http://www.wilpf.org/corp/ACP/CP_article+timeline.pdf

Views

Information

Search

This site made manifest by dadaIMC software