Baltimore IMC : http://www.baltimoreimc.org

LOCAL Commentary :: Activism : Culture : Labor

Woody and Michael: Review of "Woody Guthrie Dreams Before Dying"

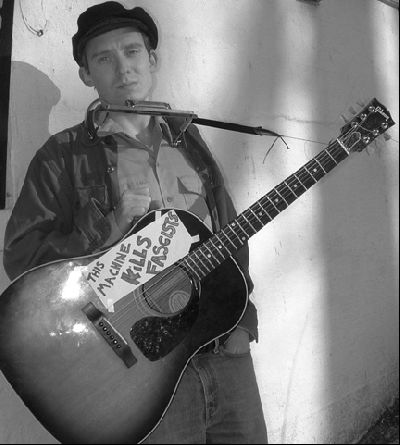

A review of Michael Patrick Smith's "Woody Guthrie Dreams Before Dying." The play, performed at Baltimore's Creative Alliance in March, 2004, featured live music and Michael Smith in the lead role as Woody Guthrie.

.

.

Woody and Michael

I attended the second and final performance of Dreams Before Dying, Michael Patrick Smith’s theatre production about the life of Woody Guthrie, on Friday, March 26th at the perpetually stimulating Creative Alliance theatre space on Eastern Boulevard. The place was packed, the audience a mix (though mostly white) of those drawn in by the feature article in the Baltimore Sun (“my, this sounds interesting, dear”) to those attuned in varying portions and degrees to (a) Woody; (b) folk music; (c) leftist politics; or (d)“this-would-never-be-at-Center-Stage” theatre. I know Michael as an ex-student, an independent spirit, and a talented actor, writer, and director. I will admit to admiring the fidelity he has to his vision what theatre can and should be.

The “facts” of Guthrie’s short sojourn on earth are full of poetic and surreal potential, all the more so the closer he drew to his death. If we all live lives that are partly truth and partly fiction, Woody was one of the first to do so publicly—and without apologizing for it. He spent the last 14 (or so) years of his life with active brain waves, but the nature of his disease made it impossible for him to speak or write or to communicate in any way what must have been the tumultuous variety of images, ideas, thoughts, and memories going on in his head. And we know--or can really only suppose we know--based on the thousand songs he wrote, the autobiography, numerous other writings, and his well-documented skills as a raconteur, that a lot was (probably) happening inside that slowly deteriorating skull.

I think that Mike saw the dramatic possibilities, the poetic potential--and the artistic freedom--of imaging the thoughts of a slowly dying artist. And the (mostly male) American mythology that Guthrie lived is a dose of inspiration for those who need it. He represents the freedom of the road, and has become the personification of the untutored poetic genius, the troubadour with a social conscience, the hard drinkin’, easy lovin’, irresistible and irrepressible sprit who did it all his way. He is America’s Pan and its Orpheus, its Danton and its Byron, a champion of the people and a slave to his own shortcomings.

To Michael’s credit, it is clear from the production that while he truly loves and admires Woody, he does not shy away from showing how the man who espoused freedom and equality could not break the chains of alcohol, and hardly ever treated women as anything more than receptacles. And it is to Michael’s credit that he focuses on what Woody should be remembered for, his artistry. The writing throughout, even when it is covering the more pedestrian aspects of Woody’s life, is above average; when Michael forgets about being historical and lets his own imagination fly, it is often humorous, touching, even inspired. And this is what I found most troublesome/annoying/boring about the production. In essence, too much time was taken in the “then Woody did this, then he did this” mode of drama.

The places where the play became more than itself were those that were based on fact, but were not factual, those scenes in which Michael expanded his stage away from the naturalistic/realistic mode into the surreal. I am thinking of the sequence about his collaboration with the Martha Graham dancers, his wild trip in the beat-up Buick, the Jesus and Stalin scenes, the play’s concluding monologue--these were full of energy and life, and I think gave a true sense of what it was to be Woody Guthrie. These scenes went below the surface; the audience saw not just Woody, but Woody in his unique social, artistic, and political environment; these scenes showed how he effected and was affected by his context. Some scenes cry out for a freer approach--his daughter’s death, for example, is presented as hurting Woody deeply, but how much better to find a way to show how that was felt in his imagination and dreams than in the mundane biographical fact of depression and withdrawal into more whiskey. I would (and have) encouraged Michael to focus on what his play says it is in his title: work on the dreams, bag the biography. This play now could easily be (with a few expletives removed) an excellent vehicle for high school assemblies. I want more than that, I think Michael does, and I know that the opportunity to create something truly unique and beautiful is there, in Woody’s life and Michael’s imagination. Michael has obviously done his research, now is the time to truly create.

As to the production qualities, the lighting design was functional and complicated--thanks should be given to Paul Kelm for his effective work, particularly with only one day to do it. The settings were fine, the staging was smooth and seamless, a noteworthy accomplishment, given the play’s many scenes and locations. Benjamin Pohlmier and Michael deserve credit for this. I would take them to task, however, for the amateurishness of some of the acting, most notably many of the women characters. It isn’t the actresses’ fault--they were obviously inexperienced and untrained. But with the surplus of fine young actresses in Baltimore, I wish more attention had been given to this aspect of the production. Beverly Shannon, who had the lionesses’ share of the women’s work in the play, was more accomplished, but was not really given much to do other than look bemused or lovingly at Woody. Both Michael and Benjamin missed opportunities to give her some complexity. Women seemed to have been very important in Woody’s life: it would be nice--at the least-- to give him a little more credit by making them more interesting, in the writing, casting, and directing of those roles.

What I saw was a fine start, a production tied too close to biography, but with intimations of possibilities. I saw the plagues of lots of theatre, weak acting and directing that settled for easy choices. I saw the efforts of a young artist who was not afraid to take on a tremendous task, one that fully engaged his intellect and passion. And if he was not totally successful, this should not be the end of this project, only an early version, and a draft of better things to come. Good artists keep at it, until they have gone beyond themselves, beyond their previous capabilities. Michael’s play about Woody is poised here, ready launch itself into the amazing unknown.

Alan Kreizenbeck, April 14, 2004

CLICK to SEE Interview with Michael Patrick Smith

.

Woody and Michael

I attended the second and final performance of Dreams Before Dying, Michael Patrick Smith’s theatre production about the life of Woody Guthrie, on Friday, March 26th at the perpetually stimulating Creative Alliance theatre space on Eastern Boulevard. The place was packed, the audience a mix (though mostly white) of those drawn in by the feature article in the Baltimore Sun (“my, this sounds interesting, dear”) to those attuned in varying portions and degrees to (a) Woody; (b) folk music; (c) leftist politics; or (d)“this-would-never-be-at-Center-Stage” theatre. I know Michael as an ex-student, an independent spirit, and a talented actor, writer, and director. I will admit to admiring the fidelity he has to his vision what theatre can and should be.

The “facts” of Guthrie’s short sojourn on earth are full of poetic and surreal potential, all the more so the closer he drew to his death. If we all live lives that are partly truth and partly fiction, Woody was one of the first to do so publicly—and without apologizing for it. He spent the last 14 (or so) years of his life with active brain waves, but the nature of his disease made it impossible for him to speak or write or to communicate in any way what must have been the tumultuous variety of images, ideas, thoughts, and memories going on in his head. And we know--or can really only suppose we know--based on the thousand songs he wrote, the autobiography, numerous other writings, and his well-documented skills as a raconteur, that a lot was (probably) happening inside that slowly deteriorating skull.

I think that Mike saw the dramatic possibilities, the poetic potential--and the artistic freedom--of imaging the thoughts of a slowly dying artist. And the (mostly male) American mythology that Guthrie lived is a dose of inspiration for those who need it. He represents the freedom of the road, and has become the personification of the untutored poetic genius, the troubadour with a social conscience, the hard drinkin’, easy lovin’, irresistible and irrepressible sprit who did it all his way. He is America’s Pan and its Orpheus, its Danton and its Byron, a champion of the people and a slave to his own shortcomings.

To Michael’s credit, it is clear from the production that while he truly loves and admires Woody, he does not shy away from showing how the man who espoused freedom and equality could not break the chains of alcohol, and hardly ever treated women as anything more than receptacles. And it is to Michael’s credit that he focuses on what Woody should be remembered for, his artistry. The writing throughout, even when it is covering the more pedestrian aspects of Woody’s life, is above average; when Michael forgets about being historical and lets his own imagination fly, it is often humorous, touching, even inspired. And this is what I found most troublesome/annoying/boring about the production. In essence, too much time was taken in the “then Woody did this, then he did this” mode of drama.

The places where the play became more than itself were those that were based on fact, but were not factual, those scenes in which Michael expanded his stage away from the naturalistic/realistic mode into the surreal. I am thinking of the sequence about his collaboration with the Martha Graham dancers, his wild trip in the beat-up Buick, the Jesus and Stalin scenes, the play’s concluding monologue--these were full of energy and life, and I think gave a true sense of what it was to be Woody Guthrie. These scenes went below the surface; the audience saw not just Woody, but Woody in his unique social, artistic, and political environment; these scenes showed how he effected and was affected by his context. Some scenes cry out for a freer approach--his daughter’s death, for example, is presented as hurting Woody deeply, but how much better to find a way to show how that was felt in his imagination and dreams than in the mundane biographical fact of depression and withdrawal into more whiskey. I would (and have) encouraged Michael to focus on what his play says it is in his title: work on the dreams, bag the biography. This play now could easily be (with a few expletives removed) an excellent vehicle for high school assemblies. I want more than that, I think Michael does, and I know that the opportunity to create something truly unique and beautiful is there, in Woody’s life and Michael’s imagination. Michael has obviously done his research, now is the time to truly create.

As to the production qualities, the lighting design was functional and complicated--thanks should be given to Paul Kelm for his effective work, particularly with only one day to do it. The settings were fine, the staging was smooth and seamless, a noteworthy accomplishment, given the play’s many scenes and locations. Benjamin Pohlmier and Michael deserve credit for this. I would take them to task, however, for the amateurishness of some of the acting, most notably many of the women characters. It isn’t the actresses’ fault--they were obviously inexperienced and untrained. But with the surplus of fine young actresses in Baltimore, I wish more attention had been given to this aspect of the production. Beverly Shannon, who had the lionesses’ share of the women’s work in the play, was more accomplished, but was not really given much to do other than look bemused or lovingly at Woody. Both Michael and Benjamin missed opportunities to give her some complexity. Women seemed to have been very important in Woody’s life: it would be nice--at the least-- to give him a little more credit by making them more interesting, in the writing, casting, and directing of those roles.

What I saw was a fine start, a production tied too close to biography, but with intimations of possibilities. I saw the plagues of lots of theatre, weak acting and directing that settled for easy choices. I saw the efforts of a young artist who was not afraid to take on a tremendous task, one that fully engaged his intellect and passion. And if he was not totally successful, this should not be the end of this project, only an early version, and a draft of better things to come. Good artists keep at it, until they have gone beyond themselves, beyond their previous capabilities. Michael’s play about Woody is poised here, ready launch itself into the amazing unknown.

Alan Kreizenbeck, April 14, 2004

CLICK to SEE Interview with Michael Patrick Smith

Views

Information

Search

This site made manifest by dadaIMC software