Baltimore IMC : http://www.baltimoreimc.org

Review :: [none]

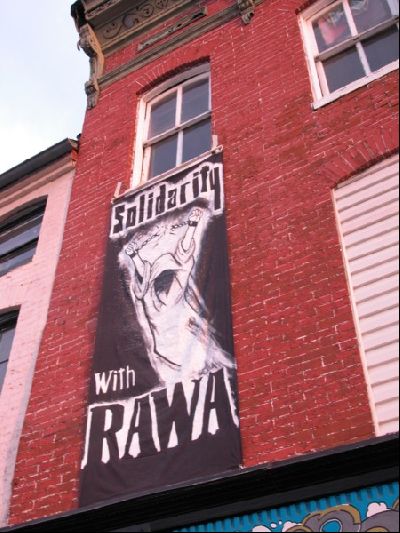

RAWA: A PORTRAIT OF STRENGTH

Anne Brodsky, Ph.D. and Associate Professor of Psychology at UMBC, has written an impressive book about the history, culture, community and stength of the Revoluationary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA). With All Our strength, The Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan is reviewed in this article. (Anne Brodsky will speak at Stoney Run Friends on September 25. See the Indymedia calendar for details.)

With All Our Strength, The Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan is an absorbing first book by Anne Brodsky, Ph.D. It reveals the anatomy of an underground organization of women opposing dangerous fundamentalist adversaries in Afghanistan. In order to write this book Brodsky traveled extensively in Pakistan and Afghanistan, braving the daily threats faced by the women of RAWA.

Brodsky’s straightforward, readable prose brings to life RAWA’s history, culture, and current struggles through the words and experiences of the women who are RAWA members and their “male supporters.” RAWA’s struggle for women’s and human rights and a secular democracy in Afghanistan is a non-violent one. As Brodsky writes, “Their weapons are their voices and their pens; their self-sacrifice and sense of community; and their commitment to social change.”

Founded in 1977, RAWA has protested and weathered the Soviet occupation, the violent Jehadi rule and the Taliban, the assasination in 1987 of their beloved leader, Meena, and since the latest American invasion, more jehadi warlords. In a country in which fundamentalist culture considers a woman to be one-half a man, life for Afghan women is extremely harsh. We’ve seen the images and heard the stories: women wearing the burqa, unable to venture outside the home without a male relative, the torture and stoning of women whose dress reveals too much bare skin, and many other visions of brutal oppression. But the author specifically rejects the view of Afghan women as "victims." Brodsky’s observations uncover the relationship between the power of women and the organization which has amplified their strength and fostered resilience to overcome enormous odds.

Through the power of community, armed with a view of incremental change, the women of RAWA have accomplished many incredible feats. In Afghanistan, they have recorded the crimes of the Taliban and other rulers. Brodsky describes a particularly horrific event, well known in the U.S. after September 11 when the oppression of Afghan women became a cause celebre.

A woman had been sentenced to death in the Taliban’s infamous soccer stadium for supposedly killing her husband. Several teams of RAWA women supported by men secretly brought a video camera to the stadium and videotaped the asassination of the woman.

This graphic video has been seen worldwide. Were it not for RAWA, this event would never have come to light. Brodsky describes the intricate underground teamwork required to pull off this heroic exploit. Had any of the many people involved been discovered for their part in this action, there is no doubt that they would have been tortured and killed.

In the refugee camps of Pakistan where many members of RAWA live and work in somewhat more freedom, they have started schools, clinics, and small businesses, organized demonstrations and rationed emergency food aid to immigrants at-risk of starvation.

Providing essential services play a role in attracting recruits and gaining trust in community. Equally important to their struggle is the acceptance of it’s protracted mature: “We in the West tend to be impatient. We don’t like waiting for our fast food, waiting in line for cash from a machine, waiting for the beep to leave a phone message, reading too long an article, or hearing too long a speech. And we expect change in the world to happen quickly as well. RAWA has a different perspective. From the very founding, early members said that this movement would be a long-term one and that the change they wanted to see for women and for Afghanistan might not be something that would happen in their lifetimes…the educational approach to change that they have taken to change that they have taken from the beginning is one that is slow, methodical, and incremental.”

Brodsky describes the approach to leadership within the RAWA membership. “The goal was to create a leadership structure that was democratic, collective, and as non-hierarchical as possible, thus promoting the equality and democracy that RAWA seeks for Afghanistan at large.” As a result, all RAWA members vote in elections to select a Leadership Council composed of 11 members. Many of these women are selected for their proven commitment to the struggle, in which actions speak louder than words.

One of the key organizing tools for RAWA is Payam-e Zan, a newspaper that is written, published and distributed by RAWA’s members. According to Brodsky, “during the Khalq and Parcham, Jehadi, and Taliban periods, members risked arrest, torture, and possible death if caught with the magazine.” Even with a free press declared in Afghanistan it is still dangerous under certain circumstances to have a copy of Payan-e Zan. The newspaper has been and continues to be a tool for political discussion and education in RAWA schools, as well as a way to heighten public discourse and to expose the fundamentalists.

According to the author, RAWA’s concept of feminism is seen within Islamic cultural norms. RAWA rejects the Western female as sex object, and questions the true liberation of Western women. Rather than viewing RAWA as an organization that needs to learn from the West, the author expresses a need to examine RAWA as a model for organization and non-violent change.

With All Our Strength, The Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan challenges the reader to question and examine the struggles of RAWA to understand how RAWA has lasted 27 years, how it has made gains under brutal conditions, and how we can adapt lessons of struggle from this tenacious and committed community of revolutionaries.

At the very least, in reading this book you will begin to see Afghan women not as the helpless, Burqa-bound creatures of a stone age culture, but as adaptable, fighting women of great courage.

Because of the absolute secrecy surrounding RAWA's membership, Brodsky changed the names of her interviewees and subjects, often excluding details of particular places and specific quantitative information. In spite of this limitation, the book does not suffer from a lack of veracity. With Brodsky's selection of interviews, annotated historical accounts, as well as the author's honest observations, All Our Strength presents a readable, authentic account of revolution in action. I felt like I knew these women personally and could learn from their experiences in challenging a harshly oppressive and violent world through peaceful means.

At a time when U.S. media has literally made Afghanistan invisible, this important book has not received the attention it deserves.

See also "A Visit to Pakistan: An Interview with Ann Brodsky" baltimore.indymedia.org/feature/display/805/index.php

Views

Information

Search

This site made manifest by dadaIMC software