Commentary :: Asia : Class : History : Military : U.S. Government

Defend North Korea! U.S. War on North Korea Never Ended

![]()

December 2010

Beginning in 1945, at the End of World War II

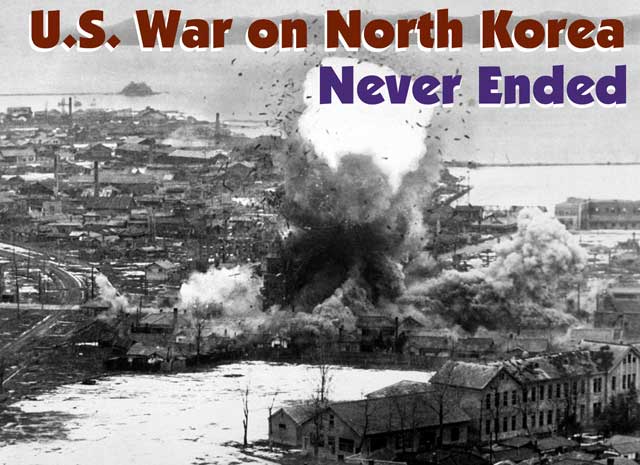

U.S. bombing of port of Wonsan in 1951. U.S. saturation bombing flattened 18 of North Korea's 22 cities, an unequaled level of destruction in modern wars. (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense)

For Revolutionary Reunification of Korea!

The American media have demonized North Korea ever since the start of the anti-Soviet Cold War following the end of World War II. It is typically portrayed like something out of a comic book – an irrational, paranoid regime constantly engaged in provocations, behaving like a petulant child, lashing out in order to get attention, immersed in a never-ending succession crisis, a hermit kingdom bent on incinerating the South and nuking Japan, if not Hawaii, while deliberately starving its own population. This caricature is nothing but crude war propaganda. In fact, it is North Korea that was incinerated by U.S. imperialism in the Korean War, and which ever since has been the object of endless provocations and nuclear threats from Washington. Even before the official start of the war in June 1950, the U.S. government vowed to “roll back Communism” in the Korean peninsula and elsewhere. During the war, it officially adopted the goal of “destruction” of North Korea. And despite the 1953 armistice, the Korean War has never stopped.

U.S. president Truman decorates Gen. MacArthur in ceremony on Wake Island, October 1950. In the background is U.S. ambassador to South Korea John Muccio, who received a medal of merit. MacArthur planned to wipe out North Korea with atom bombs. Muccio sent letter saying it was official policy to fire on refugees. (Photo: AP)

U.S. president Truman decorates Gen. MacArthur in ceremony on Wake Island, October 1950. In the background is U.S. ambassador to South Korea John Muccio, who received a medal of merit. MacArthur planned to wipe out North Korea with atom bombs. Muccio sent letter saying it was official policy to fire on refugees. (Photo: AP)

During the fighting, General Douglas MacArthur prepared to hit North Korea with dozens of atomic bombs; in 1951, President Harry Truman signed off on the plan to nuke the North if Communist forces pushed further South. In 1969, Richard Nixon put nuclear-armed warplanes on 15-minute alert and had Henry Kissinger order the Pentagon to come up with scenarios for using the hundreds of U.S. warheads pre-positioned in South Korea. In the 1990s, Bill Clinton weighed a nuclear strike against North Korea’s nuclear facilities and set up task forces to plan for “end game” in North Korea, which Hillary Clinton is still pursuing as Secretary of State. In 2002, George W. Bush listed North Korea as one of his so-called “axis of evil,” a hit list of “rogue regimes” slated for annihilation once Washington had bumped off Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Currently, the Obama administration is escalating its pressure on North Korea, tightening an economic blockade and staging provocative U.S.-South Korean war “games” just off its Western coast. No matter whether Democrats or Republicans are in office, U.S. rulers have been scheming about how to destroy North Korea for more than six decades.

Contrary to its political supporters, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is not socialist but a bureaucratically deformed workers state modeled on the Stalinized Soviet Union. It is similar in its fundamentals to China, Vietnam and Cuba, albeit with its own peculiar features – notably an extreme “cult of the personality” that has morphed into a dynastic succession. Its official ideology of juche – self-reliance – is simply an extreme version of the national autarky inherent in the Stalinist dogma of “building socialism in one country.” But the relatively privileged position of the Northern bureaucracy and the vagaries of the Kim family hardly bother U.S. rulers, who have for decades propped up a regime of mass murdering colonial puppets in the South. North Korea’s original sin, in the U.S.’ eyes, was overthrowing capitalist rule – for which “crime” Washington has constantly sought to topple the regime, or failing that, to obliterate the entire country. Trotskyists, in contrast, unconditionally defend North Korea against imperialism and internal counterrevolution, while seeking to oust its conservative, nationalist Stalinist ruling stratum through a proletarian political revolution in the North and revolutionary reunification of Korea.

1945-49: Imperialist Occupation and Massacres in the South

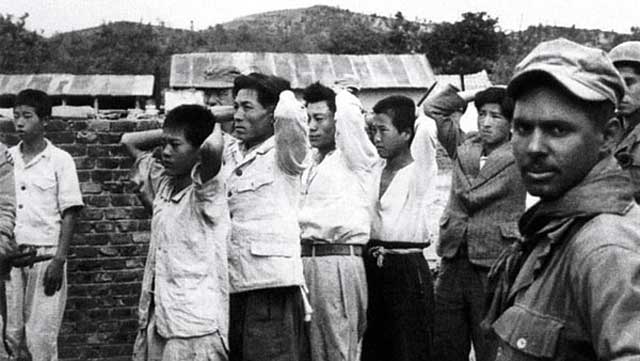

Suspected “communist collaborators” arrested in Yongdong.

Suspected “communist collaborators” arrested in Yongdong.

As World War II ended abruptly after the horrific U.S. atom-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the Soviet Army rapidly pushed the Japanese army out of Manchuria and northern Korea. It stopped at the 38th Parallel north of Seoul, in accordance with the August 1945 Potsdam agreement that carved up Soviet and Western spheres of interest worldwide. At the same time, Korean Communists led by Kim Il Sung, who had fought the Japanese colonial occupiers in guerrilla struggles since the 1930s, rapidly expanded their influence throughout the peninsula, even setting up a short-lived People’s Republic of Korea (PRK). The U.S. military government brought in Syngman Rhee from the U.S. to head a right-wing “democratic council” in the South, whose apparatus consisted of the puppets who ran Korea as a Japanese colony from 1910 to 1945. The U.S. proceeded to repress the left, banning strikes and outlawing PRK authorities in December 1945.

But this didn’t stop the spread of unrest in the South. Unlike other countries occupied by the U.S. after WWII (Germany, Japan, Austria), Korea was not a defeated imperialist power but a colonized nation yearning to throw off foreign rule. In 1946, an Autumn Uprising broke out with a peasant revolt against hated landowners, a railroad strike and mass assaults on police stations. The U.S. military government declared martial law. Although in 1945 it was agreed that after a five-year “trusteeship,” Korea would be reunited and independent, with the start of the Cold War, Washington reneged on this pledge. In March 1948, the U.S. announced elections for an anti-Communist government in the South. When the Workers Party of Korea (WPK) held rallies to oppose this, the U.S. arrested 2,500 Communist cadres. In April, South Korean police on the island of Cheju (or Jeju) fired on a demonstration commemorating the struggle against Japanese rule, touching off a mass rebellion that was put down with bloody terror:

“Over the next year, the soldiers burned hundreds of ‘red villages’ and raped and tortured countless islanders, eventually killing as many as 60,000 people – one fifth of Cheju's population. They committed these atrocities in plain view of the highest authority then in southern Korea – the U.S. military, which had occupied the peninsula south of the 38th parallel following the World War II defeat of Japan. The Americans documented the brutality, but never intervened.”

–“Ghosts of Cheju,” Newsweek, 19 June 2000

Prisoners on island of Cheju awaiting execution in 1948.

Prisoners on island of Cheju awaiting execution in 1948.

For the next 50 years, it was a crime to even mention the Cheju Massacre in South Korea, but it was only one of several. A new Republic of Korea quickly passed a National Traitors Act outlawing the WPK, forcing Communist militants to head to the hills to begin guerrilla struggle. In October 1948, a rebellion in the southwestern cities of Yeosu and Suncheon was crushed by U.S.-led forces which killed up to 2,000 civilians. In December 1949, South Korean troops in Mungyeong executed scores of prisoners (mostly children and elderly people) accused of collaborating with Communist bands. Meanwhile, the U.S. authorities were revamping their worldwide strategy for the Cold War, shifting from “containment” of Communism, the watchword of the early years, to “rolling back” the Soviet bloc, a policy embodied in National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68), issued in April 1950. The first place this doctrine was tried was in the Korean War, which broke out that June.

Newsweekquoted University of Chicago historian Bruce Cummings on the origin of the Korean War:

“Americans remember it as a lightning bolt in the morning, like the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor…. In fact, the war began as a civil conflict in 1945 – and still hasn't ended.”

In response to the proclamation of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the South, a Democratic People’s Republic (DPRK) was established in the North. Later in 1948, Soviet troops left North Korea, and in mid-1949 U.S. troops pulled out of the South. However, South Korean strong man Rhee (who opposed the U.S. withdrawal) was acutely aware that his survival depended on an American military presence, especially following the victory of the Chinese Communists against Chiang Kai-shek that October. So throughout 1949 and early 1950, the ROK army staged provocative raids across the 38th Parallel which everyone (including North Korea and U.S. officials) understood were intended to provoke a DPRK counterattack that would force the return of U.S. troops.

At the same time, Kim Il Sung and Korean nationalists, angered at the Americans’ ripping up of the 1945 agreement for a reunified Korea in five years time, saw the departure of U.S. troops as an opportunity to reunify the country by sweeping away the hated landlord/militarist regime in the South. When its forces were sufficiently built up, and assured of Soviet and Chinese backing, on 25 June 1950 the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched the attack. The “ROK” army, which had been a garrison police force under the Japanese, was no match for the KPA, which included 60,000 battle-hardened soldiers who had fought with the Chinese Communists in the just concluded civil war. As the KPA rolled south, they were welcomed by uprisings in several provinces. Rhee responded as always, ordering the execution of 30,000 prisoners accused of Communist ties, as well as tens of thousands more who had been forced into an official “re-education” campaign, called the Bodo League. Adding it up, just this past summer the New York Times (10 July) reported that a South Korean commission:

“…confirmed that during the first chaotic weeks of the war, when North Korean troops barreled down the peninsula, the South’s military and police rounded up thousands of suspected leftists – historians say as many as 200,000 – and executed them to prevent them from aiding the invading forces.”

Korean War: More U.S. Massacres in South Korea

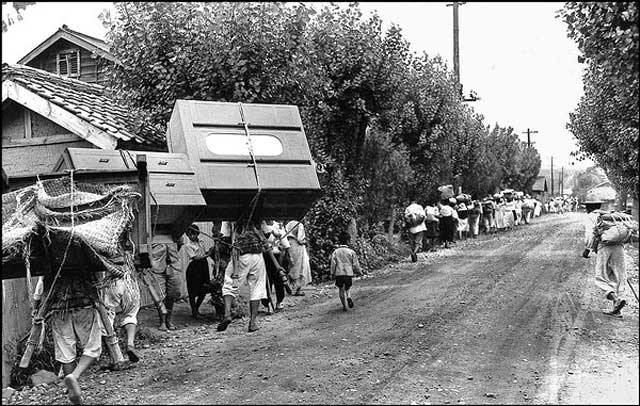

Long lines of refugees fleeing from Yongdong on 26 July 1950. The day before, hundreds of refugees were massacred by U.S. soldiers and warplanes at bridge at No Gun Ri, eight miles away. (Photo: AP)

Long lines of refugees fleeing from Yongdong on 26 July 1950. The day before, hundreds of refugees were massacred by U.S. soldiers and warplanes at bridge at No Gun Ri, eight miles away. (Photo: AP)

The prewar (1946-49) massacres by the U.S.’ South Korean flunkeys (sometimes overseen by American officers) were only the warm-up to the wholesale slaughter of Koreans carried out directly by the U.S. military during the Korean War, as American warplanes and troops returned, this time supposedly as “United Nations” forces. In the name of “freedom” and “democracy,” the United States engaged in mass murder in Korea on an industrial scale from 1950 to 1953. This included leveling virtually every city in North Korea with carpet bombing; targeting civilian population centers with firebombs and dropping huge quantities of napalm (jellied gasoline), burning inhabitants to a crisp; executing vast numbers of peasants and “suspected Communists” in cold blood; and deliberately murdering thousands of refugees. This was a policy of mass extermination. The United States wiped out one fifth of the entire North Korean population at the time. In addition, Washington prepared to drop scores of atomic bombs on the North and turn the country into a vast radioactive cemetery.

Scene of the crime: railroad bridge where hundreds of South Korean refugees were massacred bty U.S. troops on 25 July 1950. (Photo: USAF aerial photo, from U.S. Department of the Army, No Gun Ri Review [January 2001])

Scene of the crime: railroad bridge where hundreds of South Korean refugees were massacred bty U.S. troops on 25 July 1950. (Photo: USAF aerial photo, from U.S. Department of the Army, No Gun Ri Review [January 2001])

For years, there was a curtain of silence about the massacres in the South. But in 1999, a team of reporters for the Associated Press – Sand-Hun Choe, Charles J. Hanley and Martha Mendoza – published a series of groundbreaking articles laying out in horrific detail a massacre on 26 July 1950 of up to 400 Korean refugees at a bridge outside No Gun Ri, near the city of Yongdong.1 The reports were based on testimony from Korean survivors and from a dozen U.S. soldiers who had participated in or witnessed the slaughter. The reports had a profoundly shocking effect. The Pentagon had been denying this and similar reports for years. At first it claimed that no troops were even in the area of No Gun Ri. But faced with the testimony of a dozen American veterans, it had to backtrack. The AP stories won a Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. Fifteen months later, the Pentagon issued a report acknowledging that large numbers of civilians were killed by soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment at No Gun Ri, though claiming it was less than 100. Nevertheless, it concluded that the carnage was “not a deliberate killing” but “an unfortunate tragedy inherent to war.”

The right-wing U.S. News & World Report tried to discredit the AP story, as did a former Seventh Cavalry officer, Robert Bateman, who published a book seeking to refute it. With information from Pentagon records, they focused on one of the vets, Edward Daily, who it turned out had fabricated his story in order to claim benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder. But the detractors admit that numerous refugees were killed, and cannot explain the testimony of 30 Korean survivors or the eleven other U.S. soldiers who had indelible memories of the massacre. “We just annihilated them,” said ex-machine gunner Norman Tinkler. “It was just wholesale slaughter,” ex-rifleman Herman Patterson told the reporters. Vets reported that a Captain Melbourne Chandler, “after speaking with superior officers by radio, had ordered machine-gunners from his heavy-weapons company to set up near the tunnel mouths and open fire.” “Chandler said, ‘The hell with all those people. Let’s get rid of all of them’” (“War’s hidden chapter: Ex-GIs Tell of Killing Korean Refugees,” AP dispatch, 23 September 1999).

A BBC report on the Korean War quoted Seventh Cavalry vet Joe Jackman about No Gun Ri: “There was a lieutenant screaming like a madman, fire on everything, ‘kill ’em all’…. I didn't know if they were soldiers or what. Kids, there was kids out there, it didn't matter what it was, eight to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot ’em all.” But this was not the action of some panicked soldiers – they were acting on orders. The original AP story quoted retired Colonel Robert Carroll, then a lieutenant, who witnessed aircraft strafing the refugees and then riflemen opening fire on the refugees: “This is right after we get orders that nobody comes through, civilian, military, nobody.” That very morning, July 26, the U.S. 8th Army radioed orders throughout the Korean front that began, “No repeat no refugees will be permitted to cross battle lines at any time.” A day earlier, the headquarters of the Fifth Air Force issued a memo (labeled “Secret”) on “Policy on Strafing Civilian Refugees.” In cold bureaucratese, it read:

“3. The army has requested that we strafe all civilian refugee parties that are noted approaching our positions.

“4. To date, we have complied with the army request in this respect.”

And on July 24, the 1st Cavalry Division HQ sent out an explicit order: “No refugees to cross the front line. Fire everyone trying to cross lines. Use discretion in case of women and children.”

Some 1,800 South Korean leftists and other prisoners were massacred near Daejeon by the ROK police over the space of three days in July 1950. (Photo: U.S. Army)

Some 1,800 South Korean leftists and other prisoners were massacred near Daejeon by the ROK police over the space of three days in July 1950. (Photo: U.S. Army)

The slaughter at No Gun Ri was only one of scores of such mass murders. A far larger massacre took place outside the city of Daejeon in the first week of July 1950, when South Korean police executed over the space of three days at least 1,800 jailed leftists and other prisoners. Altogether some 4,000 civilians were murdered in Daejeon by the retreating ROK forces. This was known at the time by the top U.S. authorities. Nevertheless, when reports of this atrocity were published by Communist journalists, the United States government denounced them as “fabrications.” The Pentagon also hid photos of this massacre for half a century by classifying them secret. Even larger numbers of South Korean leftists were executed, an estimated 10,000, in the city of Busan (Pusan) during this same period (July-August 1950). Documents show that a U.S. advisor to the ROK military authorized the machine-gunning of 3,500 prisoners in Busan. An extensive presentation of evidence about the Daejeon massacre, using material uncovered by the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission, “Mass Killings in Korea: Commission Probes Hidden History of 1950,” was prepared by the Associated Press and is available on the Internet (click on link above).

On 26-29 July 1950, U.S. soldiers and planes slaughtered more than 100 people in a massacre at Chugok village in Yongdong county. On August 3, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, Maj. Gen. Hobart Gay ordered a bridge crossing the Naktong River in South Korea blown up in order to stop refugees crossing it. Gay later wrote to a military historian, “up in the air with the bridge went hundreds of refugees.” The same day, 25 miles downstream at the village of Tuksong-Dong, army engineers blew up a second bridge over the Naktong. The detonation “lifted up and turned it sideways and it was full of refugees end to end,” said Leon Denis, one of the engineers (“Other Incidents of Refugees Killed by GIs During Korea Retreat,” AP dispatch, 13 October 1999). More incidents kept coming to light. On 20 January 1951, in Youngchun American bombers dropped incendiary bombs at the mouth of a cave, killing 300 local villagers huddled inside. “Earlier that week, 60 miles to the west, another 300 South Korean refugees were killed by a U.S. air attack as they jammed a storage house at the village of Doon-po,” the AP journalists reported in a third dispatch (28 December 1999). A colleague reported seeing “the frozen bodies of at least 200 Koreans in civilian clothes” on 26 January 1951 on a road near the village of Yong-in.

Infantry massacres, aerial bombing, even the Navy got in on the indiscriminate slaughter. Years later, researchers found records in the National Archives of a massacre on a beach near the southern Korean port of Pohang. On 1 September 1950, the destroyer USS DeHaven “received orders from the SFCP [shore fire control party] to open fire on a large group of refugee personnel located on the beach,” according to the ship’s log. The ship’s officers questioned the order, but then complied. The AP (13 April 2007) reported: “‘The sea was a pool of blood,’ said Choi Il-chool, 75. ‘Dead bodies lay all over the place.’ Witnesses say 100 to 200 civilians were killed in the Navy shelling.” On 20 August 1950, a U.S. air attack on 2,000 refugees assembled at Haman, near Masan, killed almost 200 (AP dispatch, 3 August 2008). On 10 September 1950, the air force dropped 93 tanks of napalm on Wolmi Island, killing 100 or more residents, according to survivors (International Herald Tribune, 21 July 2008).

No Gun Ri, Daejong, Busan, Chugok, Tuksong-Dong, Youngchun, Doon-po, Yong-in, Pohang, Haman, Wilmi Island, the bridge over the Naktong River: these names should be seared into the collective memory as horrendous massacres committed by U.S. forces in the Korean War. And these are only some of the ones in which 100 or more dead are reported. There are countless others in which dozens and scores were machine-gunned, strafed, napalmed and fire-bombed.

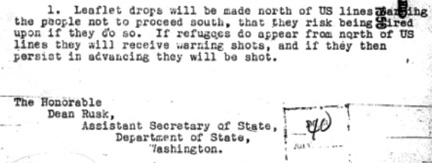

Excerpt from 26 July 1950 letter from U.S. ambassador John Muccio to Ass’t. Sec. of State Dean Rusk reporting official U.S. policy that refugees approaching U.S. lines will be shot.

Excerpt from 26 July 1950 letter from U.S. ambassador John Muccio to Ass’t. Sec. of State Dean Rusk reporting official U.S. policy that refugees approaching U.S. lines will be shot.

Like the infamous 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam, these were not the actions of some lone lieutenant – they were the result of official policy.In 2006, a former Harvard historian now at the National Archives, Sahr Conway-Lanz, discovered a letter from the U.S. ambassador to Korea, John Muccio, to his superior, Assistant Secretary of State Dean Rusk, sent the night before the No Gun Ri massacre. It reported on a high-level meeting with military commanders and outlined the policy: “If refugees do appear from north of US lines they will receive warning shots, and if they then persist in advancing they will be shot” (see “U.S. Policy Was to Shoot Korean Refugees,” AP dispatch, 29 May 2006). So there is not the slightest doubt that the top U.S. military authorities in Korea directly ordered the deliberate killing of non-combatant refugees, an unambiguous war crime, and that this was known by civilian authorities in Washington. Yet no one has ever been tried, or even charged, for this mass murder.

For decades, right-wing dictatorships in South Korea and the United States government kept a lid on all reports of mass killings by their armed forces. But in December 2005, under a liberal government in Seoul under President Roh Moo-hyun, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up to investigate mass killings going back to the period of Japanese colonial rule. It had more than 200 wartime cases on its docket. Last summer, it was reported that the Commission had found that “American troops killed groups of South Korean civilians on 138 separate occasions during the Korean War.” But now a right-wing government headed by Lee Myung-bak is in office determined to wrap up the commission without antagonizing the U.S. So with new commissioners in charge, the slaughter was written off as due to “military necessity.” No compensation will be sought or criminal charges filed in 97 percent of the cases brought before the body, and the survivors will get nothing. So much for “truth” and “reconciliation.”

Korean War: Napalm and Nuke Threats in the North

Napalm bombing of village near Hanchon, North Korea, 10 May 1951. Use of napalm on villages later became infamous in Vietnam, but much more was dumped on North Korea. (Photo: AP)

Napalm bombing of village near Hanchon, North Korea, 10 May 1951. Use of napalm on villages later became infamous in Vietnam, but much more was dumped on North Korea. (Photo: AP)

In the South, the U.S. forces engaged in retail level mass murder, mowing down hundreds of civilians at a time. As the U.S. Army (along with ROK troops and contingents from Britain and Turkey) crossed the 38th Parallel invading the North, they turned to wholesale slaughter of thousands and tens of thousands of North Koreans, treating the entire population as “the enemy.” This was billed as a “limited war” but it was under the command of Gen. MacArthur, who advocated total war against Communism – and had waged it against Japan. Even after he was relieved of his command for insubordination in April 1951, MacArthur’s policies were continued. The preeminent historian of the Korean War, Bruce Cumings, has written:

Map: warchat.org

Map: warchat.org

“The air force dropped 625 tons of bombs over North Korea on 12 August [1950], a tonnage that would have required a fleet of 250 B-17s in the second world war. By late August B-29 formations were dropping 800 tons a day on the North. Much of it was pure napalm. From June to late October 1950, B-29s unloaded 866,914 gallons of napalm.”

–“Korea: Forgotten Nuclear Threats,” Le Monde Diplomatique (English edition), December 2004

From the outset, the aim was to wipe out every urban center in the North. In his recent book, The Korean War: A History (Modern Library, 2010), Cummings notes:

“The United States dropped 635,000 tons of bombs in Korea (not counting 32,557 tons of napalm), compared to 503,000 tons in the entire Pacific theater in World War II…. [A]t least 50 percent of eighteen out of the North’s twenty-two major cities were obliterated.”

Responding to apologists for this devastation, Cummings points to the implicit racism behind it: “note the logic: they are savages, so that gives us the right to shower napalm on innocents.”

To comprehend the scope of the destruction of North Korea by U.S. air power, consider some comparisons. In Germany, estimates of the number of civilians killed in the Allied air war range from 305,000 (U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey) to 600,000, out of a total German population of 78 million. The bombing aimed at destroying the Reich’s industrial capacity and breaking morale (which it notoriously failed to do) through sheer terror. (This, from the “democratic” imperialists who today claim to be waging a “war on terror”!). Where the civilian population was targeted with firebombing – notably Hamburg and Dresden – this was widely denounced as war crimes. In Japan, due to racist prejudice the U.S. rulers had fewer compunctions about indiscriminately slaughtering Asian, rather than European (“white”) civilians (see John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War [Pantheon Books, 1986]). Some 100,000 people were killed in a single firebombing raid on Tokyo in March 1945, and more than 200,000 were murdered in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that August. In Japan, estimates of civilian deaths range up to 600,000, out of a total population of 72 million – the same scope as in Germany, but over a much shorter time period of nine months.

Pyongyang, capital of North Korea, in 1953, almost entirely destroyed by U.S. bombing during the Korean War.

Pyongyang, capital of North Korea, in 1953, almost entirely destroyed by U.S. bombing during the Korean War.

In North Korea, in contrast, the U.S. bombing went on for three years, and its purpose was not terrorizing the population, it was annihilation. Cumings quotes Curtis LeMay, the architect of the aerial bombing that incinerated Japanese cites (and who later advocated bombing Vietnam “back to the Stone Age”). LeMay says he argued with his Pentagon superiors at the outset to “let us go up there . . . and burn down five of the biggest towns in North Korea.” While there were objections about civilian casualties, he said, in the end “over a period of three years or so . . . we burned down every town in North Korea and South Korea, too.” The number of civilian dead in North Korea during the war was over 1 million, and total casualties of 1.5 million-plus, out of a total population at the time of 8-9 million: almost 20 percent of the population. Plus another million killed in South Korea.

When the revelations came out about the massacre at No Gun Ri and other cases of mass murder by U.S. forces in South Korea, the ministry of foreign affairs of the DPRK put out a memorandum (21 March 2000) detailing the slaughter carried out by the imperialists in the North. A main target was the capital, Pyongyang, which was 75 percent destroyed by aerial bombing. The memo reported: “During the war, the U.S. aggressors made more than 1,400 air raids on Pyongyang dropping over 428,000 bombs, destroying all industrial establishments, educational, health and public service facilities and dwelling houses and killing many innocent civilians.” In just one of those raids, on 11-12 July 1952, U.S. planes dropped over 6,000 napalm bombs, killing some 8,000 people. They also hit other Northern cities repeatedly, including Nampho, Hamhung, Hungnam, Sinuiju and Chongjin, burning them to the ground. Overall, the memo stated, “Napalm and other bombs dropped by U.S. warplanes totaled nearly 600,000 tons, which was 3.7 times the 161,425 tons of bombs they dropped over Japan proper during the Pacific War,” although North Korea is only one-third the size of Japan.

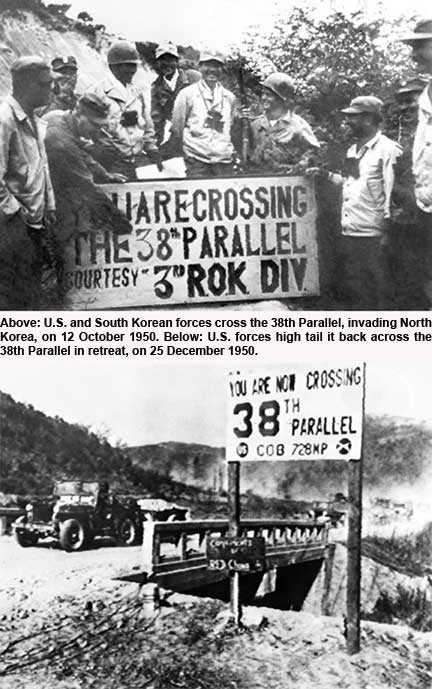

While the North’s KPA rapidly defeated the South Korean army early in the war (July-August 1950), as soon as the United States reinvaded in force in September (in the guise of a United Nations “police action”), the balance of forces shifted dramatically. In a few weeks, the U.S./“U.N.” army pushed the overextended KPA back to the north. But when Americans crossed the partition line at the 38th Parallel on 1 October 1950, the military balance shifted again. China sent a People’s Volunteer Army of 1 million troops to aid their North Korean comrades. Under the illusion that they were still advancing, the U.S. Eighth Army launched a “Home by Christmas Offensive” on November 25. Instead, by December 25 the entire U.S./U.N. force had been pushed out of North Korea. As it retreated, it adopted a scorched earth policy, destroying everything and everyone in its path.

While the North’s KPA rapidly defeated the South Korean army early in the war (July-August 1950), as soon as the United States reinvaded in force in September (in the guise of a United Nations “police action”), the balance of forces shifted dramatically. In a few weeks, the U.S./“U.N.” army pushed the overextended KPA back to the north. But when Americans crossed the partition line at the 38th Parallel on 1 October 1950, the military balance shifted again. China sent a People’s Volunteer Army of 1 million troops to aid their North Korean comrades. Under the illusion that they were still advancing, the U.S. Eighth Army launched a “Home by Christmas Offensive” on November 25. Instead, by December 25 the entire U.S./U.N. force had been pushed out of North Korea. As it retreated, it adopted a scorched earth policy, destroying everything and everyone in its path.

During its brief (October to mid-December 1950) occupation of the North, the U.S. escalated the indiscriminate massacres it had carried out in the South. A museum in Sinchon¸ where the slaughter was particularly intense, documents many of these, including over 1,500 people blown up or burned to death in air raid shelters in the city from October 17 to 20; 2,000 people shot, bayoneted and pushed off Sokdang Bridge over a period of three weeks; and another 900 (including 500 women and children) massacred on December 7. Altogether, over 35,000 civilians were killed in the Sinchon region, a quarter of the entire population. Elsewhere, on November 7, they shot to death more than 500 civilians on Mt. Sudo in Haeju, and another 600 in Haugogae valley in Kumsan. On December 5 in Sariwon City they arrested and took 950 inhabitants to Mt. Mara, then machine-gunned them to death. When the U.S. military entered the North Korean capital of Pyongyang, they jailed 4,000 civilians and shot 2,000 of them in the prison yard. For a listing of these horrific murders, see the section on the DPRK of the report of the Korea International War Crimes Tribunal (held on 23 June 2001 in New York).

But that’s only (some of) what the U.S. did. What it was preparing to do was far worse. After MacArthur had been pushed out of the North, on 24 December 1950, the U.S./U.N. commander made a formal request for 38 atomic bombs accompanied by a list of 24 targets, to turn North Korea from a wasteland (which U.S. bombing had already made it) into an uninhabitable moonscape. In posthumously published interviews, MacArthur claimed he had a plan to win the war in ten days: “I would have dropped 30 or so atomic bombs . . . strung across the neck of Manchuria,” leaving “behind us – from the Sea of Japan to the Yellow Sea – a belt of radioactive cobalt . . . it has an active life of between 60 and 120 years. For at least 60 years there could have been no land invasion of Korea from the North.”2 Or any human life in Korea north of the 38th parallel.

This was a program for genocide on a scale surpassing Hitler.Was it just bluster from a general known as a braggart? Not at all. On 30 November 1950, President Truman (who had ordered the A-bombing of Japan) threatened in a news conference to use any weapon in the U.S. arsenal. Many considered this a slip of the tongue. It was not. The same day, an order was issued to the Strategic Air Command to prepare to dispatch bomb groups to the Far East with “atomic capabilities.” Earlier, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had estimated that atomic bombs could establish “a cordon sanitaire … in a strip in Manchuria immediately north of the Korean border.” This was exactly MacArthur’s doomsday scenario, minus the cobalt bombs (which didn’t exist).

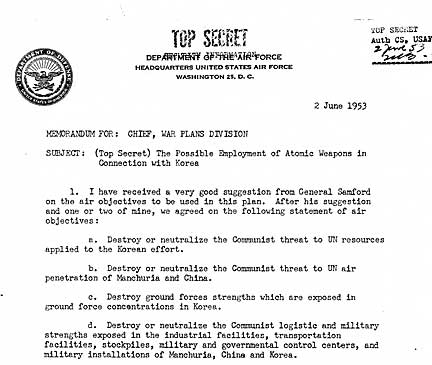

And not just in North Korea. Note that plan referred to in memo to chief of war plans for the U.S. Air Force included nuking industry and government centers in Manchuria and China, as well as Korea.

And not just in North Korea. Note that plan referred to in memo to chief of war plans for the U.S. Air Force included nuking industry and government centers in Manchuria and China, as well as Korea.

Cummings reports that “The US came closest to using atomic weapons in April 1951, when Truman removed MacArthur [as commander in chief in Korea]…. Truman traded MacArthur for his atomic policies.” In March, the atomic bomb loading operation at the U.S. air base on Okinawa became operational; the bombs were there, and only had to be assembled. On April 5, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered immediate atomic retaliation against Manchurian bases if large numbers of new Chinese forces entered the fighting. That same day, the head of the Atomic Energy Commission began the process of transferring Mark IV nuclear capsules to the Ninth Air Force for use in Korea. Only Chinese restraint apparently stopped this operational plan. In June 1951 the JCS again considered using A-bombs, this time for tactical battlefield purposes. And in October 1951, U.S. forces carried out “Operation Hudson Harbor,” a simulated atomic bombing including weapons assembly and sending lone B-29 aircraft from Okinawa to North Korea to drop dummy A-bombs or heavy TNT bombs as a trial run for using nuclear weapons.

Plans for nuking North Korea didn’t stop with the 1953 armistice, which ended the fighting but left tens of thousands of U.S. troops occupying South Korea (29,000 are still there). This past June, on the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War, the National Security Archive (a group dedicated to “piercing the self-serving veils of government secrecy”) published a series of documents on planning by the Nixon administration following the North Korean shootdown of a U.S. EC-121 spy plane in April 1969. Codenamed “Freedom Drop,” the plan called for “the selective use of tactical nuclear weapons against North Korea,” with warheads ranging from 10 to 70 kilotons each against a dozen airfields. This was hardly abstract: in 1967, the U.S. had 950 nuclear weapons stockpiled in South Korea, in flagrant violation of the Korean Armistice Agreement which banned (in Paragraph 13d) the introduction of any new weaponry. During the 1969 crisis, “nuclear-armed U.S. warplanes stood by in South Korea on 15-minute alert to strike the north.” (AP dispatch, 9 October 2010). The plan was eventually shelved after concluding that it would likely lead to all-out war, bringing in the Soviet Union.

U.S. Imperialists Going for “Endgame” in North Korea?

Again in the 1990s, the Clinton administration considered “surgical strikes” against North Korean facilities after the DPRK threatened to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.3 Ultimately the plan was dropped in favor of negotiation. Why? First, the North Korean army is a formidable force of 1 million soldiers, backed up by another 8 million reservists. It has double the manpower, more armor and substantially more artillery than the South Korean and U.S. forces in the theater. If full-scale fighting broke out, the South Korean capital, located only 35 miles from the Demilitarized Zone, could be pounded to smithereens by well dug-in North Korean artillery. The war would be fought not in the desert like the 1991 attack on Iraq, but in the suburbs or in the center of Seoul, producing millions of refugees and a staggering death toll. Second, even the right-wing South Korean government was not eager for a war. It worried about the tremendous economic cost to it of a collapse of the DPRK. Moreover, some in the ROK military were not adverse to North Korea developing nuclear weapons, figuring they would inherit them in the event of reunification. And an all-out war would likely bring in China on the other side, with untold consequences.

Again in the 1990s, the Clinton administration considered “surgical strikes” against North Korean facilities after the DPRK threatened to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.3 Ultimately the plan was dropped in favor of negotiation. Why? First, the North Korean army is a formidable force of 1 million soldiers, backed up by another 8 million reservists. It has double the manpower, more armor and substantially more artillery than the South Korean and U.S. forces in the theater. If full-scale fighting broke out, the South Korean capital, located only 35 miles from the Demilitarized Zone, could be pounded to smithereens by well dug-in North Korean artillery. The war would be fought not in the desert like the 1991 attack on Iraq, but in the suburbs or in the center of Seoul, producing millions of refugees and a staggering death toll. Second, even the right-wing South Korean government was not eager for a war. It worried about the tremendous economic cost to it of a collapse of the DPRK. Moreover, some in the ROK military were not adverse to North Korea developing nuclear weapons, figuring they would inherit them in the event of reunification. And an all-out war would likely bring in China on the other side, with untold consequences.

So once again, the U.S. attack plans were archived, but the threat remained. The Clinton administration negotiated an “Agreed Framework,” promising a regular supply of fuel oil and delivery of two light-water reactors in exchange for North Korea abandoning its plutonium enrichment efforts. However, the funds for the reactors were never appropriated, and the oil supply was soon cut off. In response, North Korea began a uranium enrichment program and eventually left the Non-Proliferation Treaty, a toothless pact aimed at keeping a monopoly of mass destruction in the hands of the dominant imperialist powers, mainly the U.S. The DPRK has developed atomic weapons and carried out at least two successful tests, in October 2006 and April 2009. It has a range of short, medium and long-range rockets capable of delivering nuclear warheads. In short, North Korea’s nuclear deterrent exists and is credible. Yet despite this, the South Korean and U.S. rulers have in the last two years sharply stepped up their pressure on the North. Again, the question must be asked: why?

On the U.S. side of the equation, Barack Obama has repeatedly pointed to North Korea as a “threat” that should be focused on. In his 2006 book Audacity of Hope, Obama asked, “Why invade Iraq and not North Korea or Burma?” (He later “clarified” this to say he wasn’t advocating invasion of North Korea.) In an article in Foreign Affairs (July-August 2007), candidate Obama called for a “strong international coalition to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons and eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons program…. In confronting these threats, I will not take the military option off the table.” Mired in a losing war in Afghanistan, the Obama administration is in no position to wage another war in northeastern Asia. Yet it is systematically stepping up military and economic pressure on the DPRK in the evident belief that “endgame” for North Korea is near.

In South Korea, the relatively liberal governments of Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) and Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008) pursued a “sunshine policy” of “engagement” with the North. But after a decade out of office, during which the liberals never dared touch the military, the right returned under President Lee Myung-bak, in the shape of the Grand National Party. This is the political instrument of the military command, which ruled South Korea uninterruptedly until the late 1990s, and the powerful chaebol conglomerates (Samsung, Hyundai, LG, etc.) who dominate industry and finance. Lee perfectly embodies this capitalist fusion of militarists and industrialists, having been installed in Hyundai by the dictator-president, Gen. Park Chung-hee. In the 2007 campaign Lee accused his predecessors of “appeasement” of the North. Since coming to office he has shown unremitting hostility to the DPRK, cutting off aid and rattling sabers at every chance. In the summer of 2009, at a meeting of Korean, Japanese and American left-wing trade-unionists, the South Koreans alerted us that following consultations in Washington and Tokyo – about whose results nothing was said publicly – South Korean president Lee had embarked on a course of provocations that could lead to war with the North.

South Korean president Lee Myung-bak donned leather jacket for tough guy image. Shown with U.S. Gen. Walter Sharp, commander of U.S. forces in Korea, during provocative joint exercises in Yellow Sea, November 29. In case of hostilities, the U.S. formally commands the Republic of Korea army. (Photo: Yonhap)

South Korean president Lee Myung-bak donned leather jacket for tough guy image. Shown with U.S. Gen. Walter Sharp, commander of U.S. forces in Korea, during provocative joint exercises in Yellow Sea, November 29. In case of hostilities, the U.S. formally commands the Republic of Korea army. (Photo: Yonhap)

The right-wing regime in Seoul is acting aggressively to push North Korea over the brink, on the supposition that with enough pressure the DPRK will implode. That is what is behind holding provocative South Korean live fire military exercises barely seven miles off the North Korean coast. A “confidential” diplomatic dispatch by the U.S. ambassador to South Korea, Kathleen Stephens, dated 12 January 2009, published by Wikileaks this week, reports that Lee is “quite comfortable with his North Korea policy and … prepared to leave the inter-Korean relations frozen until the end of his term in office, if necessary. It is also our assessment that Lee’s more conservative advisors and supporters see the current standoff as a genuine opportunity to push and further weaken the North, even if this might involve considerable brinkmanship.” One of those advisors is the former vice foreign minister Chun Yung-woo, who has now been promoted to Lee’s national security advisor.

A Wikileaks cable from Ambassador Stephens (22 February 2010) quotes Chun saying that “The DPRK … had already collapsed economically and would collapse politically two to three years after the death of Kim Jong-il.” Chun also “claimed [Chinese] Vice Foreign Minister Cui Tiankai and another senior PRC [People’s Republic of China] official from the younger generation both believed Korea should be unified under ROK control,” and that they “were ready to ‘face the new reality’” that “the DPRK now had little value to China as a buffer state.” Chun argued that while China would “not welcome” U.S. forces north of the DMZ, he “dismissed the prospect of a possible PRC military intervention in the event of a DPRK collapse, noting that China's strategic economic interests now lie with the United States, Japan, and South Korea – not North Korea.”

Saner observers have ridiculed these reports, saying “much of the information in the outed memos amounts to little more than dinner party chatter that reflects outdated opinion or wishful thinking” (Barbara Demick, “Beijing support for Korea reunification not so clear, despite leaked cables,” Los Angeles Times, 30 November). For China to stand by as an army of 1 million is removed that is the main obstacle standing between it and front-line U.S. forces, would be militarily suicidal. Moreover, counterrevolution on its doorstep would be a direct threat to the Chinese deformed workers state – something that the imperialists (and quite a few leftists) who think that China has already gone capitalist, cannot grasp. China’s refusal to condemn North Korea over the recent incidents, driving Hillary Clinton into a frenzy, show that the Stalinist leaders in Beijing have some grasp of this reality. But the U.S. and its South Korean allies may believe that their chitchat about Chinese acquiescence to a South Korean takeover of the North is accurate, and are acting accordingly. If so, the chances of renewed military aggression against the DPRK have sharply escalated, and with it the danger of a third imperialist world war.

Ailing North Korean leader Kim Jong Il (right) and son Kim Jong Un, his heir apparent, with North Korean generals reviewing troops, 10 October 2010. (Photo: Xinhua)

Ailing North Korean leader Kim Jong Il (right) and son Kim Jong Un, his heir apparent, with North Korean generals reviewing troops, 10 October 2010. (Photo: Xinhua)

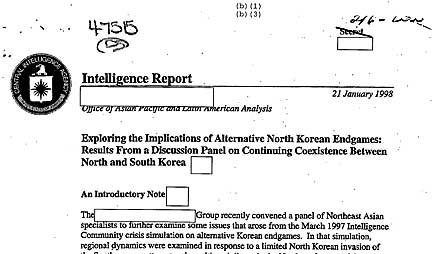

U.S. strategists have often predicted the imminent collapse of North Korea in the past. In 1997, a CIA panel of experts concluded that “the Kim regime cannot remain viable” – due to its deteriorating economic condition – “beyond five years.” (In 2006, the National Security Archive published this paper, “Exploring the Implications of Alternative North Korean Endgames,” and a series of other documents from the Clinton administration under the skeptical title, “North Korea’s Collapse? The End Is Near – Maybe.”) Likewise, an article by Robert Kaplan reported that “Middle- and upper-middle-level U.S. officers based in South Korea and Japan are planning for a meltdown of North Korea” (“When North Korea Falls,” The Atlantic, October 2006).4 The prevalent opinion among imperialist liberals has for some time been that the North Korean economy is a shambles, and now that that the ailing Kim Jong Il has introduced his son Kim Jong Un as heir apparent they see a succession crisis. This view is repeated as well by social-democratic reformists such as the International Socialist Organization (ISO), which writes of North Korea that “its economy is on the edge of collapse” (Socialist Worker, 29 November).5

The accuracy of this picture is open to question. A number of recent reports from the North indicate that markets are functioning, the population is making do as they have done for years under U.N. sanctions, most consumer goods are domestically produced, and while there are still food shortages they had a fairly good harvest this year. Over the years there have been numerous premature announcements of the impeding collapse of North Korea. In fact, the dispatches released by WikiLeaks from 2009 and early 2010 bear an uncanny resemblance to the U.S. diplomatic and intelligence analyses from the last time power changed hands in Pyongyang, in 1994, when Kim Jong Il succeeded his father, Kim Il Sung. And the analysts all agree that the North Korean bureaucracy shows “no signs of losing its political will to stay the course” (CIA analysis, 1998). Unlike the Soviet bloc Stalinists, DPRK leaders can have no illusions that they could emerge as leaders of a capitalist North Korea. They are faced with an economically and militarily powerful capitalist South Korea, whose leaders are bent on revenge – sort of Cuban gusanos with state power – and would see DPRK leaders shot than make any kind of a deal.

Whether endgame is looming for North Korea is debatable. What is true is that the Stalinist regime ultimately has no way out. What’s posed is a struggle for revolutionary reunification.

For Revolutionary Reunification of Korea:

Political Revolution in the North, Social Revolution in the South

It is impossible to learn anything about North Korea from the bourgeois press, which has demonized the country and the Kim regime like no other. Even serious imperialist publications like the London Economist (27 November) write such utter nonsense as, “No government anywhere subjects its own people to such a barbarous regime of fear, repression and hunger.” Similarly for statements like “North Korea is the poorest country in the world.” Like poorer than Somalia? (To the extent that such absurd claims are intended seriously, they are statistical flim-flam, comparing the DPRK, where housing, transportation and food are distributed by social mechanisms, with countries based on a capitalist market. Thus according to the Economist, using black market exchange rates, the average North Korean wage in 2008 was US$1 a month – a sheer impossibility.) No one reading this drivel would have a clue that the DPRK is a modern industrial country, where people work in factories and offices, have TV sets and VCRs, live in high-rise apartments, play in parks, ride in subways and on locally manufactured trolleybuses, etc.

“The poorest country in the world”? Wonsan in September 2008. (Photo: Shih-Tung Ngian)

“The poorest country in the world”? Wonsan in September 2008. (Photo: Shih-Tung Ngian)

And who exactly is subjecting the North Korean population to hunger? In the first place, there are wild claims that 2 million or even 3 million people died (the latter figure from the demonic North Korea-basher Jasper Becker) in famines in the mid-late 1990s. There certainly was widespread hunger at the time, some 60 percent of North Korean children under 5 years of age were underweight. But while the U.S. government’s Centers for Disease Control (CDC) spread blatant lies that that food consumption had fallen to under 1,000 calories a day, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the U.N. estimated the caloric intake at between 2,100 and 2,200: seriously deficient, but hardly mass starvation. As we have written,

“Contrary to imperialist propaganda about the North Korean population being reduced to eating grass, due to food rationing there have been no credible reports of mass starvation, as there certainly would have been in any capitalist country facing similarly drastic food shortages.”

–“U.S. Tries to Starve North Korea Into Collapse,” The Internationalist No. 15, January-February 2003

Yes, there was a famine and widespread malnutrition in the 1990s, but the reports of millions of North Koreans starving to death are pure invention. The food shortages were the result of a combination of bad weather (severe flooding made much of the limited farmland unusable) and the cutoff of oil supplies and export markets as a consequence of the counterrevolutionary collapse of the Soviet Union, North Korea’s main trading partner and source of aid. Prior to that, the DPRK had a productive, highly mechanized agriculture, using tractors and industrial fertilizer. With energy supplies cut off, industrial production shut down and tractors sat idle in the fields. And yes, there was someone deliberately trying to starve the North Korean people: it was U.S. imperialism under Bill Clinton, which cut off delivery of heavy oil supplies the United States was obligated to deliver, in the midst of the brutally cold Korean winter.

We Trotskyists of the League for the Fourth International are no fans of the Stalinist North Korean regime. As we have written: “The Kim dynasty is surely one of the most bizarre nationalist varieties of Stalinism on the planet. The ‘cult of the personality’ in North Korea rivals that of Stalin or Mao. For sheer capriciousness and intrusiveness the Kims rivaled the Ceausescu family in Romania, although the latter’s bloody downfall was due in good part to its efforts to pay off loans from Western bankers, plunging the country into darkness for lack of energy.” But our opposition to the bureaucratic regime of the Korean Workers Party is the exact opposite of that of the imperialists and their South Korean allies. The latter want to get rid of the Kims and the KWP in order to restore capitalism; in contrast, we warn that the bureaucracy’s attempts to appease the capitalists endanger revolutionary gains.

After years of an “Army First” policy, the DPRK has declared its focus is on building a strong economy and expanding consumer goods production by 2012. But its attempt at an economic reform in November 2009 was a fiasco, wiping out functionaries’ savings with a currency reform which limited the amount that could be exchanged while leaving intact private traders’ hoards of dollars and euros. As a result, the architect of the reform, Pak Nam Ki was reportedly executed by a firing squad after being found guilty of “deliberately ruining the national economy” (Los Angeles Times, 25 March). No doubt this was intended by the bureaucracy to show that they took seriously popular discontent over the botched reform, but it does tend to dampen discussion of policy differences if the consequence of having the wrong line means getting shot. One more reason why Trotskyists oppose the death penalty not only under capitalism – where it serves as a measure of racist repression – but also in countries where capitalist rule has been overthrown.

Botched North Korean currency reform in November 2009 sparked popular unrest, wiping out savings of many functionaries. (Photo: Shih-Tung Ngian)

Botched North Korean currency reform in November 2009 sparked popular unrest, wiping out savings of many functionaries. (Photo: Shih-Tung Ngian)

By abolishing capitalist exploitation and establishing a collectivized economy, the DPRK was able to make tremendous strides in recovering from the utter devastation of the Korean War. Pyongyang and other cities were rebuilt from the ground up, with modern housing and facilities. Up to the mid-late 1970s, North Korean workers had a higher standard of living than those south of the DMZ, as Korean capitalists accumulated capital through ruthless superexploitation of South Korean workers under the iron heel of the military regime. But ultimately, as Marx and Engels insisted as long ago as 1847 and as Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky stressed from the early 1920s on, it is not possible to build socialism in national isolation from the world (capitalist) market. A classless society can only be built on the basis of abundance, for otherwise “want is generalized” and some kind of police regime will arise to decide the distribution of scarce goods. That is the origin of the bureaucratically degenerated (in the case of the Soviet Union) and deformed workers states. If “socialism in one country” could not last in the case of the USSR with its vast resources, it certainly won’t work in a tiny half-country like North Korea starved of vital inputs.

That is why the very real gains from the overthrow of capitalism in North Korea – which lay the basis for a rationally planned economy – can only be defended by extending the revolution to the South, and to the industrial powerhouse of imperialist Japan. This requires a proletarian political revolution to oust the bureaucracy, whose capricious mismanagement undercuts the social gains in order to protect its privileged status. An authentic, Leninist-Trotskyist communist party is needed to establish a regime of egalitarianism and revolutionary workers democracy, based on councils (soviets) that can recall officials at any time. In a divided land like Korea, such an upheaval in the North can only succeed if it goes hand in hand with a social revolution in the capitalist South, to break the power of the kill-crazed militarists and expropriate the profit-crazed chaebols and other capitalists. A political revolution in Pyongyang would also send a powerful stimulus to the Chinese workers to rise up and smash the growing danger of counterrevolution as capitalist exploitation takes root and spreads.

Meanwhile, with North Korea having been subjected to countless massacres by the U.S. and its Southern puppets; having already lived through a U.S. war of annihilation that engulfed the northern half of the peninsula; and having been repeatedly threatened with nuclear attack by the U.S., it’s hardly surprising that the DPRK should seek to develop nuclear weapons in self-defense, as it has prudently done. As internationalist communists,Trotskyists defend North Korea’s acquisition of a nuclear deterrent and emphasize that the current war hysteria makes thedefense of North Korea against imperialism and counterrevolution all the more urgent. ■

U.S. gearing up for its next invasion. U.S. and South Korean military stage dramatic reenactment of 1950 Inchon landing, using 14,000 troops, September 15. (Photo: AP)

U.S. gearing up for its next invasion. U.S. and South Korean military stage dramatic reenactment of 1950 Inchon landing, using 14,000 troops, September 15. (Photo: AP)

1 The reports were later published as a book by Choe, Hanley and Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare From the Korean War (Henry Holt, 2001).

2 Quoted in Bruce Cumings, “Korea: forgotten nuclear threats,” Le Monde Diplomatique (English edition), December 2004.

3 See our article, “Defend North Korea Against Nuclear Blackmail and War Threats!” The Internationalist No. 15, January-February 2003 for a detailed analysis.

4 Kaplan is not just another liberal journalist. His book, Balkan Ghosts (1993), reportedly influenced Bill Clinton’s two wars on Yugoslavia (1995 and 1999). He is currently on the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board.

5 The intellectual godfather of the ISO, Tony Cliff, broke with the Trotskyist Fourth International in declaring the Soviet Union to be “state capitalist” at the onset of the anti-Soviet Cold War, and then in 1950 refusing to defend North Korea against the U.S.-led imperialist forces in the Korean War.

Views

Information

Search

This site made manifest by dadaIMC software