Baltimore IMC : http://www.baltimoreimc.org

Commentary :: Race and Ethnicity

John Hope Franklin: The Passing of a Griot

Franklin was born amidst the flames and terrors of the infamous race riots that consumed Tulsa, Oklahoma, once the center of Black wealth and business success. The papers and even books called it a race riot, but it was actually an anti-Black pogrom by state and private racists in envy of Black Tulsa's achievements.

Radio essay

Click on image for a larger version

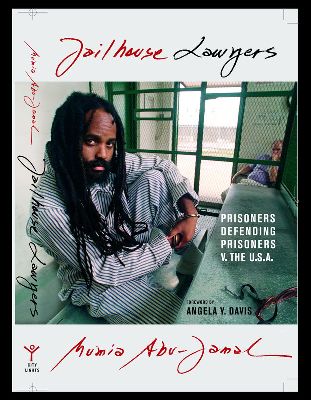

April 24, 7pm, Baltimore Event for Mumia

In solidarity with similar events around the US, there will be an event celebrating the release of death-row journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal's new book:

The Cork Gallery / 4th Floor North (Buzzer #9) / 302 E. Federal (at Guilford) / Baltimore, MD 21202

In solidarity with similar events around the US, there will be an event celebrating the release of death-row journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal's new book:

The Cork Gallery / 4th Floor North (Buzzer #9) / 302 E. Federal (at Guilford) / Baltimore, MD 21202

John Hope Franklin: The Passing of a Griot

[col. writ. 3/29/09] (c) '09 Mumia Abu-Jamal

For historians of every stripe, the name John Hope Franklin (1915-2009) is one that cannot be ignored. This is, in part, because he was past president of the American Historical Association ((AHA), a group of American scholars that has been in existence since 1884.

But his distinction arises from his work in the vineyards of American history, as a corrective to the lies about U.S. slavery, through his 1947 classic, From Slavery to Freedom, which considered with the work of late radical historian, Herbert Aptheker's 'American Negro Slave Revolts,' served to abolish the white-washing of American history that generations of historians inflicted on generations of American students.

Franklin was born amidst the flames and terrors of the infamous race riots that consumed Tulsa, Oklahoma, once the center of Black wealth and business success. The papers and even books called it a race riot, but it was actually an anti-Black pogrom by state and private racists in envy of Black Tulsa's achievements.

That his classic work, From Slavery to Freedom, is still in print today, over 1/2 a century since its initial publication is a testament to his historic brilliance.

Still, that wasn't my favorite work of his. In 1999, Franklin and one of his former students, Loren Schweninger, published Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (Oxford Univ. Press). It's both fascinating, and given its grim subject matter, surprisingly funny in its uncovering of dozens of hidden stories from slavery days.

Franklin and Schweninger mined the private letters of slaveholders to unearth their real concerns. In an April 7, 1829 letter from Louisiana cotton planter, Joseph Bieller, he complains bitterly about the slave's practice of 'swinging' his pigs. Wrote Bieller, "I have had a very seveer time among my negroes.... they have bin Swinging my hogs and pigs."

Bieller meant captives were tying up, treeing and swinging his pigs until they were badly damaged. In other words, one form of property was destroying another form of property.

Also, Franklin's work illustrates, through reprint of runaway ads in the newspapers, that all kinds of captives fled their captivity; as shown by the descriptions used to describe them, like: "intelligent", "witty", "quick-witted", "proud", "shrewd", and "keen", just to name a few. Among them were every strata of slave life: young, old, male, female, African, mixed, rebel, Uncle Tom, well-treated or whipped. Everybody wanted freedom.

And perhaps this was Franklin's robust contribution -- the thirst for freedom that bubbled in Black hearts from 1619 to the present.

John Hope Franklin was 94.

--(c) '09 maj

www.prisonradio.org/mumia.htm

[col. writ. 3/29/09] (c) '09 Mumia Abu-Jamal

For historians of every stripe, the name John Hope Franklin (1915-2009) is one that cannot be ignored. This is, in part, because he was past president of the American Historical Association ((AHA), a group of American scholars that has been in existence since 1884.

But his distinction arises from his work in the vineyards of American history, as a corrective to the lies about U.S. slavery, through his 1947 classic, From Slavery to Freedom, which considered with the work of late radical historian, Herbert Aptheker's 'American Negro Slave Revolts,' served to abolish the white-washing of American history that generations of historians inflicted on generations of American students.

Franklin was born amidst the flames and terrors of the infamous race riots that consumed Tulsa, Oklahoma, once the center of Black wealth and business success. The papers and even books called it a race riot, but it was actually an anti-Black pogrom by state and private racists in envy of Black Tulsa's achievements.

That his classic work, From Slavery to Freedom, is still in print today, over 1/2 a century since its initial publication is a testament to his historic brilliance.

Still, that wasn't my favorite work of his. In 1999, Franklin and one of his former students, Loren Schweninger, published Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (Oxford Univ. Press). It's both fascinating, and given its grim subject matter, surprisingly funny in its uncovering of dozens of hidden stories from slavery days.

Franklin and Schweninger mined the private letters of slaveholders to unearth their real concerns. In an April 7, 1829 letter from Louisiana cotton planter, Joseph Bieller, he complains bitterly about the slave's practice of 'swinging' his pigs. Wrote Bieller, "I have had a very seveer time among my negroes.... they have bin Swinging my hogs and pigs."

Bieller meant captives were tying up, treeing and swinging his pigs until they were badly damaged. In other words, one form of property was destroying another form of property.

Also, Franklin's work illustrates, through reprint of runaway ads in the newspapers, that all kinds of captives fled their captivity; as shown by the descriptions used to describe them, like: "intelligent", "witty", "quick-witted", "proud", "shrewd", and "keen", just to name a few. Among them were every strata of slave life: young, old, male, female, African, mixed, rebel, Uncle Tom, well-treated or whipped. Everybody wanted freedom.

And perhaps this was Franklin's robust contribution -- the thirst for freedom that bubbled in Black hearts from 1619 to the present.

John Hope Franklin was 94.

--(c) '09 maj

www.prisonradio.org/mumia.htm

Views

Information

Search

This site made manifest by dadaIMC software